Liver Biopsy Procedure

Written By

Yusela Aquino

Written By

Yusela Aquino

If your doctor has recommended a liver biopsy, you probably have questions. What exactly happens during the procedure? Will it hurt? How long does recovery take?

A liver biopsy is one of the most valuable diagnostic tools available for evaluating liver disease. While blood tests and imaging scans provide important information, examining actual liver tissue under a microscope gives doctors insights that no other test can match.

In this comprehensive guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about the liver biopsy procedure—from preparation through recovery. Whether you’re scheduled for a biopsy soon or simply researching your options, understanding the process can help ease anxiety and ensure you’re fully prepared.

Quick overview of a liver biopsy procedure

A liver biopsy is a short procedure where a doctor removes a small piece of liver tissue using a specialized needle. This tissue sample is then sent to a pathology lab for microscopic analysis. The entire process helps diagnose various liver conditions that might not be detectable through other diagnostic tests.

Most modern liver biopsies are performed as same-day outpatient procedures at a hospital or outpatient center. You’ll typically arrive in the morning and go home that afternoon.

Here’s the timing breakdown:

-

Actual needle time: Less than one second per sample

-

Total procedure time: 15-90 minutes depending on the type

-

Full visit duration: Approximately half a day, including preparation and recovery monitoring

The three main approaches to liver biopsy include:

-

Percutaneous biopsy: A needle passes through the skin into the liver (most common method)

-

Transjugular biopsy: A catheter enters through a neck vein for patients with bleeding disorders or severe ascites

-

Surgical or laparoscopic biopsy: Performed during another operation or when direct visualization is needed

The type of liver biopsy your doctor recommends depends on your bleeding risk, anatomy, presence of fluid in the abdomen, and other medical considerations.

The specific steps of the liver biopsy procedure and the recovery process may vary depending on your health care provider's practices, which can influence preparation, monitoring, and aftercare.

What is a liver biopsy?

A liver biopsy involves removing a small core of liver tissue—typically 1-2 centimeters long and about 1-2 millimeters wide—for examination under a microscope by a pathologist. This tiny sample of liver tissue contains thousands of liver cells and provides a detailed snapshot of your liver’s health.

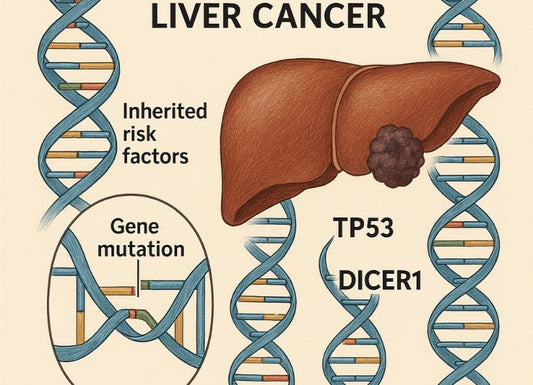

During the microscopic examination, the pathologist looks for signs of damage or disease, including conditions such as hepatitis (inflammation of the liver), cancer, or other abnormalities. Specifically, the pathologist examines for:

-

Inflammation: Swelling and immune cell activity that may indicate hepatitis or autoimmune disease

-

Fibrosis and scar tissue: Progressive scarring that can lead to cirrhosis

-

Fat accumulation: Excess fat deposits seen in fatty liver conditions

-

Tumors or abnormal cells: Cancer cells or other abnormal cells that may indicate liver cancer or other malignancies

-

Storage disorders: Abnormal accumulation of substances like iron or copper

A liver biopsy can be used to diagnose hepatitis, which is inflammation of the liver.

A biopsy provides more detailed information than blood tests or imaging tests alone. While blood work can suggest liver disease is present, and imaging can show structural changes, only a biopsy can confirm exactly what’s happening at the cellular level.

Liver biopsies have been performed routinely since the 1950s. Over the decades, techniques have become significantly safer with the introduction of ultrasound and CT scan guidance, which allow doctors to precisely target the safest needle path.

Types of liver biopsy procedures

There are three main clinical techniques for obtaining a liver tissue sample: percutaneous (through the skin), transjugular (through a neck vein), and surgical (open or laparoscopic).

Percutaneous biopsy is the most common method worldwide. It’s appropriate for most patients with acceptable blood clotting and no significant fluid accumulation in the abdomen.

Transjugular biopsy (also called transvenous liver biopsy) is chosen for people with blood clotting problems, significant ascites, or when measuring liver vein pressures is clinically important.

Surgical or laparoscopic liver biopsy is typically performed during another planned operation rather than as a standalone test. This approach is used when direct visualization of the liver surface is particularly valuable.

Percutaneous liver biopsy

The percutaneous approach—sometimes called percutaneous liver biopsy or simply percutaneous biopsy—is the technique used for most patients who need a liver biopsy.

Here’s how it works:

-

The doctor numbs the skin and deeper tissues with a local anesthetic, then passes a thin biopsy needle between the ribs on the right side of your upper abdomen

-

Ultrasound guidance is typically used before and during the procedure to identify a safe entry path that avoids blood vessels and lung tissue

-

You’ll usually lie on your back or be slightly turned to the left, with your right arm raised above your head to widen the spaces between your ribs

-

At the key moment, you’ll be asked to breathe in, fully exhale, and hold your breath for a few seconds while the needle quickly takes one or more samples

-

The entire procedure generally takes less than 15-20 minutes, with the needle actually inside the liver for less than one second per sample

The biopsy needle used—typically a 16- to 18-gauge cutting needle—rapidly removes a thin core of tissue with minimal trauma to the surrounding liver.

Transjugular liver biopsy

Transjugular liver biopsy takes a different approach, accessing the liver through the venous system rather than through the abdominal wall.

The procedure begins with a small puncture in the right side of the neck to enter the internal jugular vein under ultrasound guidance. From there:

-

A thin catheter is threaded through the jugular vein, down through the chest, and into the hepatic veins inside the liver

-

Continuous X-ray imaging (fluoroscopy) guides the catheter into the correct position

-

A specialized biopsy needle passes through the catheter to collect tissue samples from within the liver

-

The samples are taken from inside the liver veins, significantly reducing the risk of bleeding into the abdominal cavity

This technique is particularly valuable for patients with advanced cirrhosis, severe ascites, or those taking blood thinners that cannot be safely stopped. The same catheter can also measure pressure differences in the liver veins—information that helps assess the severity of portal hypertension.

The transjugular approach has a low complication rate, with capsule bleeding occurring in approximately 0.6% of cases.

Surgical or laparoscopic liver biopsy

Surgical liver biopsy and laparoscopic liver biopsy are typically performed under general anesthesia in an operating room, usually as part of another planned surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery approach:

-

Small incisions are made in the abdominal wall

-

A camera (laparoscope) is inserted, allowing the surgeon to view the liver on a video screen

-

Instruments are used to take targeted samples from visible lesions or representative areas

-

Carbon dioxide gas is used to create space in the abdomen for visualization

Open surgical biopsy:

-

A larger incision provides direct access to the liver surface

-

The surgeon can take larger or multiple samples as needed

-

This approach offers immediate ability to control any bleeding

Surgical biopsy may be done when a biopsy may be done during tumor removal, liver transplant evaluation, or gallbladder surgery. Recovery time depends on the overall surgery, not just the biopsy component.

Why doctors recommend a liver biopsy

Doctors order a liver biopsy when blood tests, imaging, or symptoms suggest liver disease but the exact cause or severity remains unclear. A biopsy provides definitive answers that guide treatment decisions.

Common diagnostic indications include:

-

Unexplained elevated liver enzymes on blood tests

-

Chronic hepatitis B or C infection requiring staging

-

Suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or steatohepatitis (metabolic syndrome is a risk factor for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MASLD, formerly NAFLD), which may prompt a liver biopsy)

-

Autoimmune hepatitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis

-

Inherited metabolic or autoimmune disease (hemochromatosis, Wilson disease)

-

Evaluation of a liver tumor, liver mass, or suspicious liver cancer

-

Unexplained enlarged liver (hepatomegaly)

-

Suspected alcoholic liver disease

-

Drug-induced liver damage

Staging and grading purposes:

-

Determining the degree of inflammation in chronic liver conditions

-

Quantifying fibrosis to assess progression toward cirrhosis

-

Guiding decisions about starting, adjusting, or stopping treatments

-

Evaluating response to antiviral therapy or immunosuppressants

Monitoring applications:

-

Assessing liver health after liver transplant

-

Confirming suspected drug-induced liver injury

-

Tracking disease progression in certain liver diseases

-

Monitoring for rejection in transplant recipients

While non-invasive alternatives like elastography and serum biomarkers have reduced the need for biopsy in some situations by 30-50%, the liver biopsy remains the gold standard when precision is critical—particularly for unexplained cases or treatment trials.

Preparing for a liver biopsy

Preparation typically starts several days before your scheduled procedure. Proper preparation helps ensure both safety and accurate results.

The process includes:

-

Reviewing all the medicines you currently take

-

Completing required blood tests

-

Following fasting instructions

-

Arranging transportation and time off work

Blood tests—including platelet count and clotting studies like INR or PT—are typically done within a few days of the biopsy. These tests check your blood’s ability to clot properly and identify any bleeding disorders.

Medication adjustments may be necessary. You may need to pause or adjust:

-

Blood thinners (warfarin, apixaban, rivaroxaban)

-

Antiplatelet medications (clopidogrel, aspirin)

-

High-dose fish oil or vitamin E supplements

-

Certain herbal products that affect blood clotting

Fasting is usually required for about 6-8 hours before the procedure, especially if sedation or anesthesia will be used. Your facility will provide specific timing instructions.

Arranging a responsible adult to drive you home is essential. Someone should stay with you for at least the first night if sedation is used.

Talking with your doctor before the biopsy

Before your procedure, have a thorough conversation with your health care provider. Key topics to discuss include:

-

Why the biopsy is specifically recommended for your situation

-

What questions the biopsy is meant to answer

-

How results might change your treatment plan

-

Complete list of prescription medicines, over-the-counter drugs, and herbal products you take

-

Any history of bleeding problems, allergies, or reactions to anesthesia

-

Whether the biopsy will be ultrasound-guided

-

What type of sedation or numbing medicine will be used

-

How pain will be controlled during and after the procedure

-

The consent form—understand the benefits, risks of a liver biopsy, and alternatives before signing

Pre-procedure tests and imaging

Standard pre-biopsy testing serves to estimate bleeding risk and plan the safest approach:

|

Test Type |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Liver function blood tests |

Assess current liver status |

|

Complete blood count |

Check platelet levels |

|

Clotting studies (INR, PT) |

Evaluate blood clotting function |

|

Abdominal ultrasound |

Assess liver size, position, and plan needle path |

|

CT scan or MRI |

Target specific nodules (if available) |

Abdominal ultrasound is often performed shortly before the biopsy. It helps identify any ascites and plan a safe biopsy site.

If tests reveal major blood clotting problems or large volumes of fluid in the abdomen, your team may switch from a percutaneous approach to a transjugular biopsy.

Fasting, medication changes, and practical arrangements

Follow these practical steps as a pre-biopsy checklist:

Fasting guidelines:

-

No solid food for 6-8 hours before the procedure

-

Clear liquids may be allowed up to a specified cutoff time

-

Follow your facility’s specific instructions

Medication adjustments:

-

Make changes to blood thinners only under medical advice

-

Discuss diabetes medicines and timing with your doctor

-

Clarify which heart medications to continue or hold

Day-of preparations:

-

Wear loose, comfortable clothing

-

Leave valuables at home

-

Bring a list of all medications and relevant medical documents

-

Arrive at your scheduled check-in time

Post-procedure planning:

-

Plan for reduced activity the rest of the day

-

Consider taking the following day off work

-

Have comfortable recovery space ready at home

What happens during a liver biopsy

On procedure day, you’ll follow a structured sequence designed to ensure your safety and comfort.

Check-in and preparation:

-

Registration and confirmation of consent

-

Vital signs measurement (blood pressure, pulse, temperature)

-

IV line placement if sedation is planned

-

Opportunity to ask final questions

Monitoring setup:

-

Blood pressure cuff attached

-

Pulse oximeter placed on your finger

-

ECG leads may be applied for heart monitoring

Local anesthesia:

-

A local anesthetic is injected into the skin and deeper tissues over the biopsy site

-

This numbing medicine eliminates sensation in the area

-

The injection is often the most uncomfortable part of the procedure

Imaging guidance:

-

Ultrasound or fluoroscopy positions the needle or catheter safely

-

Real-time imaging reduces the risk of accidental injury to blood vessels or organs

Sample collection and completion:

-

Once the tissue sample is obtained, pressure is applied to the site

-

A sterile bandage covers the puncture

-

The sample goes to the pathology lab with your clinical information

Step-by-step: percutaneous biopsy procedure

-

Positioning: You lie on your back or slightly on your left side on the procedure bed. Your right arm goes above your head to widen rib spaces.

-

Preparation: The skin over your right upper abdomen is cleaned with antiseptic. Sterile drapes are placed around the area.

-

Anesthesia: Local anesthetic is injected between the ribs on the right side. You’ll feel mild pain or stinging for a few seconds.

-

Needle insertion: A small skin nick may be made, then the biopsy needle advances quickly into and out of the liver.

-

Breath-holding: You’ll be coached to hold your breath at a specific moment. This reduces liver movement and improves sampling accuracy.

-

Sample collection: Usually one or two passes are enough. Each pass lasts less than one second.

-

Pressure and bandaging: Immediately after needle removal, firm hand pressure is applied for several minutes. A bandage covers the site.

Step-by-step: transjugular biopsy procedure

-

Positioning: You lie on your back on the procedure table.

-

Neck preparation: The right side of your neck is cleaned and numbed with local anesthetic.

-

Vein access: A small puncture enters the internal jugular vein using ultrasound guidance.

-

Catheter threading: A thin catheter passes through the neck vein, down through your chest, and into the hepatic veins. X-ray fluoroscopy guides this process.

-

Contrast injection: Contrast dye may be injected to visualize the vessels clearly.

-

Sampling: A special side-cutting biopsy needle passes through the catheter to take several small samples. You remain mostly still and breathe normally.

-

Catheter removal: The catheter and sheath are removed. Pressure is held at the neck puncture.

-

Bandaging: A small bandage covers the neck site.

Overall time in the procedure room is usually 45-90 minutes, particularly if pressure measurements are also taken.

Step-by-step: surgical or laparoscopic biopsy

For surgical or laparoscopic liver biopsy, you receive general anesthesia and are fully asleep throughout.

Laparoscopic approach:

-

Small incisions are made in the abdominal wall

-

A camera and instruments are inserted

-

The surgeon visually inspects the liver surface on a video screen

-

Targeted samples are taken from visible lesions or representative areas

-

Any bleeding can be immediately controlled

Open surgical approach:

-

A larger incision provides direct liver access

-

Multiple or larger biopsies can be taken as needed

-

The surgeon directly visualizes the liver surface

Surgical biopsy is typically part of a broader operation—for example, removal of a liver tumor, transplant evaluation, or gallbladder surgery—rather than a standalone outpatient test. Recovery depends on the overall surgery.

Anesthesia, sedation, and pain during a liver biopsy

Most percutaneous and transjugular liver biopsies use local anesthetic to numb the area, with optional light sedation to help you relax. This approach keeps you comfortable while allowing you to follow instructions like holding your breath.

General anesthesia—where you’re fully unconscious—is typically reserved for:

-

Surgical or laparoscopic biopsies

-

Procedures combined with other major operations

-

Patients who cannot tolerate being awake

When only local anesthesia and mild sedatives are used, you remain able to communicate with the medical team throughout the procedure.

Typical sensations during the procedure:

-

Brief stinging or burning during the anesthetic injection

-

Pressure or dull aching when the needle passes through the liver capsule

-

Possible sensation of the needle “thump” even with good numbing

Additional pain medicine can be given afterward if needed. Most people describe the overall discomfort as moderate and short-lived.

How painful is a liver biopsy?

Pain is the most common concern patients have before a liver biopsy. Here’s what to realistically expect:

During the procedure:

-

The sharpest pain is usually the local anesthetic injection, lasting only a few seconds

-

The actual biopsy needle is often felt as quick pressure rather than sharp pain

-

Effective numbing significantly reduces sensation during tissue collection

After the procedure:

-

Some patients experience referred pain to the right shoulder (the liver capsule and diaphragm share nerve pathways)

-

Most post-procedure pain is mild to moderate

-

Discomfort typically peaks within the first few hours

-

Oral pain medicines or other pain medicines usually provide adequate relief

When to be concerned: Report severe, worsening, or persistent pain to your medical team. While you may feel mild pain that’s normal, intense pain can sometimes signal complications like excessive bleeding or bile leakage.

What to expect after the procedure

After your biopsy, you’ll be moved to a recovery area where nurses monitor your condition at regular intervals. You will be monitored for several hours after the liver biopsy to check for complications, and a blood sample may be taken a few hours after the procedure to check for internal bleeding.

You will be asked to rest quietly in a recovery room for 1 to 2 hours after the biopsy.

Monitoring includes:

-

Blood pressure checks

-

Heart rate monitoring

-

Breathing assessment

-

Pain level evaluation

Observation times vary by procedure type:

|

Biopsy Type |

Typical Observation Time |

|---|---|

|

Percutaneous |

2-4 hours |

|

Transjugular |

4-6 hours |

|

High-risk patients |

Extended as needed |

During recovery, you’ll likely be asked to lie on your right side or flat for at least 1-2 hours. This position helps compress the liver and reduce bleeding risk.

Most people go home the same day. However, you should not:

-

Drive yourself home

-

Operate machinery

-

Sign important documents

-

Make major decisions until sedation effects fully clear

Results are often available in a few days to about a week, but timing varies by facility and case complexity.

Activity, wound care, and medications after biopsy

Follow these post-biopsy care guidelines for optimal recovery:

Activity restrictions:

-

Avoid heavy lifting for 5-7 days

-

No vigorous exercise or contact sports during this period

-

Longer restrictions may apply per your doctor’s advice

-

Light desk work is usually fine within 1-2 days if you feel well

Wound care:

-

Keep the bandage dry for 24 hours

-

Follow specific instructions for showering and bandage removal

-

Watch the biopsy site for signs of increasing redness or swelling

Medications:

-

Use only pain medicines approved by your care team

-

Avoid high-dose NSAIDs like ibuprofen unless specifically allowed

-

Resume regular medications as directed

General recovery:

-

Rest quietly for the remainder of the procedure day

-

Stay well-hydrated

-

Eat light meals as tolerated

Warning signs and when to seek urgent care

Most complications appear within the first 24 hours, but monitoring should continue for several days. Seek immediate medical attention if you experience:

Abdominal symptoms:

-

Sudden severe abdominal or shoulder pain

-

Increasing swelling or firmness in your abdomen

-

Possible internal blood loss signs

Cardiovascular signs:

-

Dizziness or fainting

-

Rapid heart rate

-

Drop in blood pressure symptoms (lightheadedness, weakness)

Breathing problems:

-

Shortness of breath (could indicate collapsed lung from accidental injury to the chest wall)

-

Difficulty taking deep breaths

Visible bleeding signs:

-

Bright red bleeding from the biopsy site

-

Soaking through the dressing with blood

-

Rectal bleeding or black/bloody stools

Systemic symptoms:

-

Fever or chills

-

Yellowing of skin or eyes

-

Signs of infection at the biopsy site

Use the emergency contact numbers provided by your hospital, or go directly to the nearest emergency department if serious symptoms occur.

Risks and possible complications of liver biopsy

Liver biopsy is generally safe when performed by experienced teams with proper imaging guidance. However, like any invasive procedure, it carries small risks that you should understand before giving consent.

Common minor issues (experienced by many patients):

-

Temporary pain at the biopsy site

-

Mild bleeding under the skin

-

Brief low-grade fever

Uncommon but serious complications:

-

Significant internal bleeding requiring intervention

-

Accidental injury to nearby organs (lung, gallbladder, kidney)

-

Bile leak from the biliary tract

-

Infection at the biopsy site

-

High blood pressure in the portal system complications

Risk statistics:

-

Major bleeding is uncommon (often <2%, but reported ranges vary by patient risk, indication, and definition.

-

Rates are higher in patients with cirrhosis.

-

Mortality is extremely rare in modern practice. Death is very rare; large reviews/guidelines commonly cite mortality under 1 in 1,000.

Careful patient selection, imaging guidance, and post-procedure monitoring help keep complication rates low. Ultrasound/CT guidance helps the team choose a safer needle path and is widely used to improve accuracy and safety.

Bleeding

Bleeding is the primary concern following liver biopsy. The risk centers on hemorrhage from the liver puncture site into the abdominal cavity.

Early warning signs of significant bleeding:

-

Worsening right-sided or shoulder pain

-

Drop in blood pressure

-

Increasing heart rate

-

Feeling lightheaded or faint

Outcomes of bleeding complications:

-

Mild bleeding often stops spontaneously with observation

-

Significant bleeding may require hospitalization

-

Blood transfusions may be needed in some cases

-

Rarely, urgent procedures or surgery are required

Higher risk groups:

-

Patients with advanced cirrhosis

-

Those with low platelet counts

-

People with abnormal lab tests for clotting

-

Patients who couldn’t stop blood thinners

This is precisely why pre-biopsy blood work and appropriate method selection are so important. Transjugular biopsy may be chosen specifically to minimize bleeding risk in high-risk patients.

Pain and other less common complications

Pain is the most common post-biopsy complaint and is usually manageable with simple painkillers and rest.

Other rare complications include:

|

Complication |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Pneumothorax |

Accidental puncture of the lung, causing collapsed lung |

|

Organ perforation |

Injury to gallbladder, kidney, or intestine |

|

Bile leakage |

Bile escaping from damaged ducts |

|

Infection |

Bacterial contamination of the biopsy site |

|

Hemobilia |

Bleeding into the bile ducts |

Transjugular-specific risks:

-

Neck hematoma at the access site

-

Reaction to contrast dye

-

Cardiac arrhythmias during catheter passage

Pre-existing conditions—such as severe heart or lung disease—may influence your individual risk profile. These factors should be discussed thoroughly with your liver specialist or interventional radiologist before the procedure.

Overall risk remains low, but personalized risk-benefit discussions are essential for informed decision-making.

Understanding your liver biopsy results and next steps

Pathology reports from liver biopsies provide detailed information about your liver’s condition. The report typically includes:

Findings described:

-

Type of liver injury present (inflammation, fat, bile duct changes, tumors)

-

Presence of abnormal lump or masses

-

Identification of specific disease patterns

Standardized scoring:

-

Grade of inflammation (activity score)

-

Stage of fibrosis (F0-F4 or similar scales)

-

Presence or absence of cirrhosis

Your treating doctor—whether a hepatologist, gastroenterologist, or surgeon—will interpret the pathology report alongside your blood tests, imaging studies, and clinical history to formulate a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Preparing for your results appointment:

-

Schedule a follow-up visit specifically to review biopsy results

-

Write down questions beforehand

-

Bring a family member or friend for support

-

Ask about implications for your prognosis

-

Discuss any new medications or lifestyle changes needed

-

Clarify what additional tests might be required

Important questions to ask:

-

What exactly did the biopsy show?

-

What stage is my liver disease?

-

What treatment options are available?

-

How often will I need liver monitoring going forward?

-

Is there a chance I might need another biopsy in the future?

Keep a personal copy of your pathology report for future reference. This document becomes part of your permanent medical record and may be valuable for other specialists you see.

While a liver biopsy plays an important role in diagnosing certain liver conditions, many people start paying attention to their liver health much earlier. At-home liver health testing, like the Ribbon Checkup kit, makes it easy to check key liver-related markers from home using a simple finger-prick blood sample. The results can help you spot potential issues sooner, track changes over time, and have more informed conversations with your healthcare provider.

At-home testing isn’t meant to replace medical care or procedures like a liver biopsy, but it can be a convenient first step for staying proactive about your health. If you’re curious about your liver health or want an easier way to monitor it between doctor visits, the Ribbon Checkup kit may be a helpful place to start.

Key takeaways

-

A liver biopsy removes a small tissue sample for microscopic analysis, providing information that blood tests and imaging cannot match

-

Percutaneous biopsy through the skin is most common, while transjugular biopsy through the jugular vein is used for patients with bleeding risks

-

Preparation includes blood tests, medication adjustments, and fasting before the procedure

-

Most biopsies take 15-90 minutes

-

Local anesthetic numbs the area; sedation is optional for most needle biopsies

-

Recovery involves 2-6 hours of monitoring, with restrictions on heavy activity for about a week

-

Complications are uncommon but include bleeding, pain, and rarely injury to nearby organs

-

Results typically arrive within 3-7 days and guide diagnosis and treatment decisions

Understanding what happens during a liver biopsy can help ease anxiety and ensure you’re well-prepared for the procedure. With proper preparation, open communication with your medical team, and adherence to post-procedure instructions, most patients find the experience more manageable than they anticipated.

If you’ve been told you need a liver biopsy, take time to discuss your specific situation with your doctor. Prepare your questions, understand the risks and benefits for your particular case, and arrange the support you’ll need for a smooth recovery.

Related Resources

- Metastatic Liver Cancer: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

- What Cancers Cause Elevated Liver Enzymes?

- Can Ultrasound Detect Liver Cancer?

References

Bae J. C. (2024). No More NAFLD: The Term Is Now MASLD. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea), 39(1), 92–94. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2024.103

Dohan, A., Guerrache, Y., Dautry, R., Boudiaf, M., Ledref, O., Sirol, M., & Soyer, P. (n.d.). Major complications due to transjugular liver biopsy: Incidence, management and outcome. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, 96(6), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2015.02.006

Neuberger, J., Patel, J., Caldwell, H., Davies, S., Hebditch, V., Hollywood, C., Hubscher, S., Karkhanis, S., Lester, W., Roslund, N., West, R., Wyatt, J. I., & Heydtmann, M. (2020). Guidelines on the use of liver biopsy in clinical practice from the British Society of Gastroenterology, the Royal College of Radiologists and the Royal College of Pathology. Gut, 69(8), 1382–1403. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321299

New MASLD Nomenclature | AASLD. (n.d.). https://www.aasld.org/new-masld-nomenclature

Rinella, M. E., Lazarus, J. V., Ratziu, V., Francque, S. M., Sanyal, A. J., Kanwal, F., Romero, D., Abdelmalek, M. F., Anstee, Q. M., Arab, J. P., Arrese, M., Bataller, R., Beuers, U., Boursier, J., Bugianesi, E., Byrne, C. D., Castro Narro, G. E., Chowdhury, A., Cortez-Pinto, H., Cryer, D. R., Cusi, K., El-Kassas, M., Klein, S., Eskridge, W., Fan, J., Gawrieh, S., Guy, C. D., Harrison, S. A., Kim, S. U., Koot, B. G., Korenjak, M., Kowdley, K. V., Lacaille, F., Loomba, R., Mitchell-Thain, R., Morgan, T. R., Powell, E. E., Roden, M., Romero-Gómez, M., Silva, M., Singh, S. P., Sookoian, S. C., Spearman, C. W., Tiniakos, D., Valenti, L., Vos, M. B., Wong, V. W.-S., Xanthakos, S., Yilmaz, Y., Younossi, Z., Hobbs, A., Villota-Rivas, M., Newsome, P. N. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Journal of Hepatology, Volume 79, Issue 6, 1542 - 1556. https://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/article/S0168-8278%2823%2900418-X/fulltext

Author information not available.