Is Fish Oil Good for Fatty Liver? Establishing Connection

Written By

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH

Written By

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH

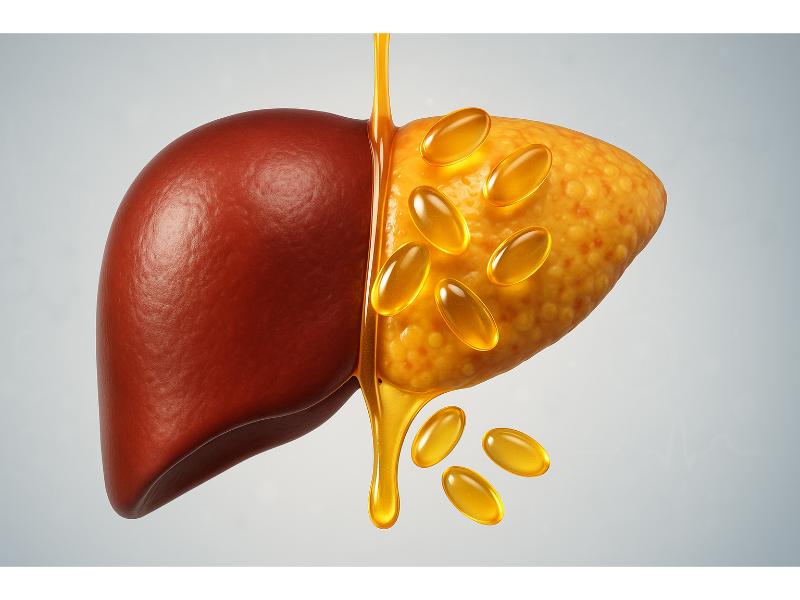

When you have been diagnosed with fatty liver, the question “is fish oil good for fatty liver” sounds normal. You don’t want to introduce something to your diet that will worsen your liver fat’s condition. But the fish’s oil omega-3 fatty acids (FA) show promise in making significant improvement in reducing liver fat. Even in the liver’s inflammation, omega-3 FAs show some benefits, as well. Though no consensus on research yet, it is worth exploring and knowing more information about. About 26.7% of adults in the US are affected by fatty liver disease, particularly Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, formerly known as NAFLD), which remains a critical concern that needs evidence-based solutions.

This article examines the science behind fish oil supplementation for liver health. It covers everything from dosage recommendation to potential risks. If you want to start fish oil supplementation, talk to your doctor before starting, especially if you have pre-existing conditions or are taking medications.

Key Insights

-

Fish oil containing EPA and DHA may reduce liver fat in some NAFLD patients, though results vary significantly between studies

-

Recommended dosage ranges from 1-3 grams of combined EPA/DHA daily, but individual needs vary based on health status

-

Common side effects include fishy aftertaste and digestive upset, while serious risks involve bleeding at high doses

-

Quality matters, choose third-party tested supplements to avoid oxidized oils that could harm liver health

-

Fish oil works best as part of comprehensive treatment including dietary changes and exercise, not as a standalone cure

Is Fish Oil Good for Fatty Liver?

Fish oil is rich in omega 3 FAs and it shows promise in reducing liver fat and inflammation in people who have fatty liver. But results vary in research—some are positively correlated, while others are often mixed. The research landscape presents a complex image where certain clinical trials demonstrate meaningful improvements in liver function markers, while some show modest or negligible effects.

The results of clinical trials consistently find omega-3 supplementation can lead to reductions in liver fat content in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). However, the quality of evidence varies considerably, with some trials suffering from small sample sizes or short durations that limit their reliability.

The mechanism behind fish oil’s potential benefits centers on its anti-inflammatory properties and ability to modulate lipid metabolism. EPA and DHA, the primary omega-3 FAs in fish oil, appear to activate specific cellular pathways that help the liver process fats more efficiently while reducing inflammatory markers associated with liver damage.

Current medical consensus suggests fish oil may serve as a valuable adjunct therapy rather than a primary treatment for fatty liver disease. Healthcare providers increasingly recommend combining omega-3 supplementation with proven interventions like:

-

Dietary modifications

-

Weight management

-

Regular exercise for optimal results

Individual responses to fish oil supplementation vary significantly based on factors including:

-

Baseline omega-3 levels in the body

-

Severity of fatty liver disease

-

Concurrent medications and health conditions

-

Diet quality and lifestyle factors

-

Genetic variations affecting omega-3 metabolism

What Is Fatty Liver Disease?

Fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, occurs when excess fat builds up in the liver, often due to obesity or poor diet, and can lead to serious complications if untreated. This condition represents a spectrum of liver disorders ranging from simple fat accumulation to severe inflammation and scarring that can progress to cirrhosis.

The disease primarily comes in two forms: alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which was renamed as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). AFLD is the result of excessive alcohol consumption occurring over time. MASLD, on the other hand, develops in people who drink little to no alcohol. NAFLD has become increasingly common, affecting an estimated 75-100 million Americans.

NAFLD progresses through several stages:

-

Simple steatosis – fat accumulation without considerable inflammation

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) – fat accumulation with inflammation and liver cell damage

-

Fibrosis – scar tissue formation in response to ongoing inflammation

-

Cirrhosis – extensive scarring that impairs liver function

The condition often develops silently, with many patients experiencing no symptoms until advanced stages. When symptoms do occur, they may include the following:

-

Fatigue

-

Abdominal discomfort

-

Unexplained or unintentional weight loss

The silent progression makes routine screening critical for early detection and intervention.

Risk factors of NAFLD mirror those for metabolic syndrome and include:

-

Type 2 diabetes

-

Obesity

-

Insulin resistance

-

High triglycerides

-

Metabolic syndrome

The rising prevalence of these conditions in the US directly correlates with increasing NAFLD rates, creating a significant public health challenge.

What Causes Fatty Liver Disease?

Common causes include metabolic factors like insulin resistance and excess calorie intake, particularly from refined carbohydrates and added sugars. The liver converts excess glucose and fructose into fat, which then accumulates within liver cells when the organ cannot process or export it efficiently.

Primary risk factors include:

-

Obesity, especially abdominal obesity

-

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

-

Insulin resistance

-

High triglyceride levels

-

Metabolic syndrome

-

Sedentary (inactive) lifestyle

-

High-calorie, processed food diet

Secondary causes include the following:

-

Certain medications (corticosteroids, some antibiotics)

-

Rapid weight loss or malnutrition

-

Genetic disorders affecting fat metabolism

The modern Western diet, characterized by high consumption of processed foods, refined sugars, and trans fats, plays a significant role in NAFLD development. Fructose consumption, particularly from high-fructose corn syrup in sodas and processed foods, appears especially problematic as the liver metabolizes fructose differently than glucose.

How Is Fatty Liver Disease Diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves blood tests for liver enzymes, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), often starting out as routine checkups when elevated liver enzymes appear on standard laboratory profiles. For extremely proactive people, they can make use of at-home urine tests, which may demonstrate some metabolites that are inherent to a damaged liver. But of course, this remains as a screening only and not as a replacement for the diagnostic process. The diagnostic process requires multiple approaches since no single test definitively diagnoses fatty liver disease.

Initial screening methods include:

-

Blood tests that measure liver enzymes like ALT, AST, and other liver enzymes

-

Lipid panels showing triglyceride and cholesterol levels

-

Glucose and insulin measurements

-

Complete metabolic profiles

Advanced imaging techniques provide more detailed and comprehensive assessments of the liver:

-

Computed tomography (CT) scans

-

MRI with spectroscopy

-

FibroScan

Liver biopsy remains the definitive diagnostic tool for distinguishing simple steatosis from NASH, though doctors reserve this invasive procedure for cases where the diagnosis remains unclear or when assessing disease severity becomes critical for treatment planning.

The diagnostic workup typically takes several weeks to complete, with blood test results available almost immediately and imaging studies scheduled based on availability and insurance approval.

When Should You Seek Help for Fatty Liver Disease?

Seek medical help if you experience fatigue, abdominal pain, or have risk factors like obesity—early detection is key to preventing progression to more serious liver conditions. Many people with fatty liver disease remain asymptomatic until advanced stages, making proactive screening essential for those with risk factors.

Warning signs that warrant immediate medical attention:

-

Persistent fatigue despite adequate rest

-

Upper right abdominal pain or discomfort

-

Unexplained weight loss

-

Yellow of skin or eyes (jaundice)

-

Swelling in legs or abdomen

-

Easy bruising or bleeding

Risk factor-based screening recommendations:

-

Yearly liver enzyme testing for people with diabetes

-

Screening every 2-3 years for those with obesity or metabolic syndrome

-

Regular monitoring for individuals taking medications that affect the liver

-

Evaluation following abnormal routine blood screening

More often, the healthcare system follows a distinct process wherein it starts with primary care evaluation. This is followed by a referral to gastroenterologists or hepatologists for specialized care when needed. The screening and follow-up evaluation allows for early detection and intervention, which significantly improve outcomes and may prevent progression to cirrhosis or liver failure.

Insurance coverage for fatty liver evaluation varies, but most plans cover initial screening tests and imaging when medically necessary. Patients could verify coverage for specialized procedures like FibroScan or MRI spectroscopy before scheduling an appointment.

What Are Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Fish Oil?

Omega-3s like EPA and DHA in fish oil are essential fats that reduce inflammation and support heart and liver health by modulating cellular processes throughout the body. These polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) cannot be produced efficiently by human cells, making dietary intake or supplementation necessary for optimal health.

The three main types of omega-3 FAs include:

-

EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) primarily supports cardiovascular and liver health

-

DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) is critical for brain function and anti-inflammatory effects

-

ALA (alpha-linolenic acid) is a plant-based omega-3 that converts poorly to EPA/DHA

Fish oil supplements concentrate on EPA and DHA from marine sources, which offer therapeutic doses that would be difficult to achieve through diet alone. The FDA recognizes omega-3 FAs as “generally recognized as safe” with established daily intake recommendations.

High quality fish oil supplements undergo molecular distillation and purification processes to remove contaminants like mercury, PCBs, and other toxins commonly found in fish. The third-party testing ensures purity and potency, with reputable manufacturers providing certificates of analysis showing contaminant levels well below FDA limits.

The supplement industry offers various forms including:

-

Triglyceride form is the naturally occurring structure from fish

-

Ethyl ester form is concentrated but less bioavailable

-

Phospholipid form is the enhanced form but at a higher cost

-

Combination products with added vitamins or antioxidants

How do Omega-3 Fatty Acids Relate to Liver Health?

Omega-3 FAs support liver health by:

-

Reducing inflammation

-

Improving fat metabolism

-

Protecting liver cells from oxidative stress

These essential fats work through multiple pathways to address the underlying mechanisms that contribute to fatty liver disease development and progression.

Key mechanisms include:

-

Activation of PPAR-α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha) pathways to promote fat burning

-

Reduction of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha) and IL-6 (interleukin-6)

-

Improved insulin sensitivity, reducing fat storage in liver cells

-

Enhanced production of specialized pro-resolving mediators that help resolve inflammation

-

Stabilization of liver cell membranes against oxidative damage

Studies show that omega-3 fatty acids can change the way genes work that control fat metabolism. This is like "reprogramming" liver cells to break down fats more efficiently. This genetic modulation occurs through epigenetic mechanisms that don’t alter DNA structure but affect how genes function.

The liver plays a central role in omega-3, converting these FAs into bioactive compounds that circulate throughout the body. Adequate omega-3 levels help maintain this conversion process, supporting not just liver health but overall metabolic function.

Clinical investigations indicate that persons with FLDs frequently have decreased baseline omega-3 levels in comparison to healthy counterparts, implying either heightened use due to inflammation or insufficient dietary intake of these beneficial lipids.

What Are the Sources of Omega-3s?

Natural resources include fatty fish like salmon and mackerel. Supplements provide concentrated EPA and DHA when dietary intake falls short of therapeutic levels. The richest food sources deliver omega-3s in their most bioavailable forms, making them preferable to supplements when possible.

Top dietary sources include:

-

Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines, anchovies)

-

Fish oil supplements

-

Cod liver oil

-

Algae oil supplements

-

Fortified foods like eggs, milk, and cereals

It is recommended to consume fish at least twice a week to meet omega-3 needs. But, therapeutic doses for FLD may require higher doses or higher intake. Farm-raised fish typically contain lower levels of omega-3 compared to wild-caught fishes due to a difference in feeding practices.

Supplement quality varies significantly among manufacturers. Look for products that:

-

Display third-party certification

-

Specify EPA and DHA content clearly on labels

-

Use sustainable fishing practices

-

Store properly to prevent rancidity

-

Provide expiration dates and storage instructions

Plant sources like flax seeds, chia seeds, and walnuts contain ALA omega-3s. But, the human body converts less than 10% of ALA to EPA and DHA. This inefficient conversion makes marine sources or algae supplements more effective for therapeutic purposes.

How Do Omega-3s Work in the Body?

Omega-3s modulate lipid metabolism and reduce inflammation via pathways like PPAR activation, essentially reprogramming how cells process fats and respond to inflammatory signals. These FAs integrate into cell membrane structures, altering membrane fluidity, and affecting numerous cellular processes.

Primary mechanisms of action:

-

Cell membrane incorporation

-

Eicosanoid production

-

Gene expression modulation

-

Insulin sensitivity improvement

-

Antioxidant enzyme activation

In the liver specifically, omega-3 fatty acids:

-

Reduce hepatic lipogenesis (new fat production)

-

Increase fatty acid oxidation (fat burning)

-

Improve VLDL export (removal of fat from the liver)

-

Decrease inflammatory cell infiltration

-

Protect hepatocytes from oxidative stress

The timeline for omega-3 effects varies by the desired outcome measure. Anti-inflammatory changes may occur within weeks, while significant improvements in liver fat content typically require 3-6 months of consistent supplementation combined with lifestyle modifications.

Studies reveal that omega-3 fatty acids influence over 100 different genes related to metabolism, inflammation, and cellular protection. This widespread genetic influence explains why omega-3s affect multiple organ systems simultaneously rather than targeting just one specific condition.

Does Fish Oil Help Reduce Liver Fat?

Yes, fish oil helps reduce liver fat but the exact percentage varies. But not all trials agree on the magnitude or consistency of these benefits. The evidence base includes both encouraging results and disappointing outcomes, reflecting the complex nature of fatty liver disease and individual variation in treatment response.

A thorough review of 18 randomized controlled trials found that taking omega-3 supplements significantly decreased liver fat content compared to a placebo. The most consistent benefits were seen in studies that used higher doses (above 2 grams daily) for longer periods of time (12 weeks or more). However, the quality of evidence varied considerably between studies.

Positive findings from key studies include:

-

Reduction in liver fat measured by MRI spectroscopy after 12 weeks of EPA/DHA supplementation

-

Improved liver enzymes such as AST and ALT

-

Better insulin sensitivity

-

Reduction in inflammatory markers

-

Enhanced liver histology scores in patients who underwent biopsy

Conflicting results arise from several factors:

-

Dose variations

-

Different EPA to DHA ratios in supplements used

-

Study duration differences

-

Baseline characteristics of participants

-

Severity of disease

-

Concurrent dietary and lifestyle interventions

However, you need to understand that supplementation alone, without lifestyle modifications, shows inconsistent results across studies.

How to Choose the Right Fish Oil Supplement?

Look for verified products with high EPA and DHA content, third-party testing for purity, and sustainable sourcing practices to ensure both quality and environmental responsibility. The supplement market varies dramatically in quality, making careful selection critical for safety and effectiveness.

Essential quality markers include:

Purity and Testing

-

Third-party certification

-

Heavy metals testing

-

PCB and dioxin analysis with undetectable levels

-

Oxidation markers within specifications

Potency and Form

-

Clear EPA and DHA content labeling (not just “fish oil”)

-

Triglyceride form preferred over ethyl esters for absorption

-

Minimal inactive ingredients and artificial additives

-

Enteric coating to reduce fishy aftertaste and improve tolerance

Manufacturing Standards

-

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)

-

FDA-registered facilities with regular inspections

-

Sustainable fishing practices

-

Molecular distillation for contaminant removal

Brand Reputation and Transparency

-

Available certificates of analysis upon request

-

Clear expiration dates and storage recommendations

-

Responsive customer service for questions

-

Published research supporting their specific formulation

There are many quality options available with different price points. Generic store brands may offer value but require careful label reading to ensure adequate EPA/DHA content.

Storage considerations significantly impact supplement quality:

-

Refrigerate after opening to prevent rancidity

-

Protect from light and heat exposure

-

Use within expiration date for full potency

-

Check for fishy odor which indicates oxidation

When Should You Take Fish Oil?

Take with meals to boost absorption and reduce side effects like nausea or fishy burps that commonly occur with omega-3 supplementation. Timing strategies can significantly impact both tolerance and therapeutic effectiveness of fish oil supplements.

Optimal timing recommendations:

With Meals:

-

Enhanced absorption when taken with dietary fats

-

Reduced gastrointestinal upset and nausea

-

Better integration with natural digestive processes

-

Improved compliance due to reduced side effects

Morning vs. Evening

-

Morning: May provide energy-supporting benefits throughout the day

-

Evening: Potentially better for those experiencing daytime digestive sensitivity

-

Split dosing: Divide larger doses between meals for steady blood levels

Medication Interactions

-

Take 2+ hours apart from blood thinners to monitor effects

-

Separate from fat-soluble vitamins which may compete for absorption

-

Coordinate with diabetes medications as omega-3s may affect blood sugar

-

Discuss timing with pharmacist if taking multiple supplements

Special Considerations

-

Empty stomach: May increase absorption but often causes side effects

-

Before exercise: Some people report better energy and reduced inflammation

-

Consistency: Same time daily helps establish routine and steady blood levels

Food combinations that boost omega-3 absorption:

-

Healthy fats like avocado, nuts, or olive oil

-

Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) taken separately

-

Avoid high-fiber meals which may reduce absorption

-

Moderate protein content supports overall nutrient utilization

Individual tolerance varies significantly, with some people handling any timing while others require specific protocols to avoid side effects. Starting with smaller doses taken with larger meals helps identify the best personal approach.

Are There Any Side Effects or Risks of Fish Oil?

Common side effects include fishy aftertaste or GI upset; risks like bleeding at high doses require medical monitoring, especially for people taking blood-thinning medications. Most adverse effects are mild and dose-dependent, resolving with dosage adjustment or improved product selection.

The safety profile of fish oil is generally favorable when used appropriately, with serious adverse events occurring primarily at very high doses or in people with specific contraindications. Understanding potential risks helps ensure safe and effective supplementation.

Reported side effects by frequency:

Common

-

Fishy aftertaste and burping

-

Mild nausea, especially when taken without food

-

Loose stools or diarrhea with higher doses

-

Bad breath with fishy odor

Less Common

-

Abdominal cramping and bloating

-

Heartburn and acid reflux

-

Skin rash or allergic reactions

-

Headaches in sensitive individuals

Rare but Serious

-

Bleeding complications at very high doses

-

Severe allergic reactions in fish-allergic individuals

-

Liver enzyme elevation (usually reversible)

-

Drug interactions affecting blood clotting

The bleeding risk may become significant for people who receive high-dose purified EPA, particularly when combined with anticoagulant medications like warfarin, aspirin, or clopidogrel. Regular monitoring of clotting parameters helps prevent complications.

Quality-related side effects often result from:

-

Oxidized (rancid) fish oil causing increased inflammation

-

Contaminants like mercury in low-quality products

-

Additives and artificial ingredients in cheaper formulations

-

Improper storage leading to degradation

Who Should Avoid Fish Oil?

Avoid if you are on blood thinners or allergic to fish without doctor approval, as these conditions significantly increase the risk of serious complications. Several medical conditions and medications create contraindications that require careful medical supervision.

Absolute contraindications include:

-

Severe fish or shellfish allergies (anaphylaxis risk)

-

Active bleeding disorders or recent major surgery

-

Scheduled surgery within 2 weeks (increased bleeding risk)

-

Severe liver disease with impaired clotting function

Relative contraindications requiring medical supervision:

-

Anticoagulant therapy (warfarin, heparin, DOACs)

-

Antiplatelet medications (aspirin, clopidogrel)

-

Diabetes with frequent hypoglycemic episodes

-

Gallbladder disease or history of pancreatitis

-

Pregnancy and breastfeeding (dosage considerations)

Quick Summary Box

-

Fish oil supplementation shows promise for fatty liver disease management through its anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA

-

The typical recommended dosage ranges from 1-3 grams daily of combined EPA/DHA, taken with meals to improve absorption and reduce side effects

-

While generally safe, fish oil can cause mild digestive upset and may increase bleeding risk at high doses, particularly for people taking blood-thinning medications

-

Quality varies significantly among products, making third-party tested, sustainably sourced supplements essential for safety and effectiveness

-

Fish oil works best as part of comprehensive treatment including dietary improvements and exercise rather than as a standalone cure, with individual results varying based on disease severity and baseline health status

Related Resources

Are Bananas Good for Fatty Liver? Things You Might Not Know

Accurate at-home liver test for comprehensive health monitoring

At-Home Liver Tests: A Comprehensive Guide

References

Amirhossein Ramezani Ahmadi, Fatemeh Shirani, Behnazi Abiri, Mansoor Siavash, Haghighi, S., & Akbari, M. (2023). Impact of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on the gene expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors-γ, α and fibroblast growth factor-21 serum levels in patients with various presentation of metabolic conditions: a GRADE assessed systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of clinical trials. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1202688

Calder, P. C. (2010). Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Processes. Nutrients, 2(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2030355

Javaid, M., Kadhim Kadhim, Bilal Bawamia, Cartlidge, T., Farag, M., & Alkhalil, M. (2024). Bleeding Risk in Patients Receiving Omega‐3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Journal of the American Heart Association, 13(10). https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.123.032390

John Hopkins Medicine. (2024). Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Www.hopkinsmedicine.org. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/nonalcoholic-fatty-liver-disease

Kris-Etherton, P. M., Harris, W. S., & Appel, L. J. (2002). Fish Consumption, Fish Oil, Omega-3 Fatty Acids, and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation, 106(21), 2747–2757. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94

Liu, M., Liu, Y., & Wang, X. (2024). Discrimination between the Triglyceride Form and the Ethyl Ester Form of Fish Oil Using Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Foods, 13(7), 1128–1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13071128

Mara Sophie Vell, Kate Townsend Creasy, Scorletti, E., Katharina Sophie Seeling, Hehl, L., Miriam Daphne Rendel, Kai Markus Schneider, & Schneider, C. V. (2023). Omega-3 intake is associated with liver disease protection. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1192099

Marino, L. (2015). Endocrine causes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 21(39), 11053. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.11053

National Institutes of Health. (2022, July 18). Office of Dietary Supplements - Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Nih.gov. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-Consumer/

National Institutes of Health. (2023, February 15). Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Nih.gov. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional/

Nordøy, A., Barstad, L., Connor, W. E., & Hatcher, L. (1991). Absorption of the n-3 eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids as ethyl esters and triglycerides by humans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53(5), 1185–1190. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/53.5.1185

Parker, H., Cohn, J., O’Connor, H., Garg, M., Caterson, I., George, J., & Johnson, N. (2019). Effect of Fish Oil Supplementation on Hepatic and Visceral Fat in Overweight Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 11(2), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020475

Rich, N. E., Oji, S., Mufti, A. R., Browning, J. D., Parikh, N. D., Odewole, M., Mayo, H., & Singal, A. G. (2018). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Prevalence, Severity, and Outcomes in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 16(2), 198-210.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.041

Rudkowska, I., Garenc, C., Couture, P., & Vohl, M.-C. (2009). Omega-3 fatty acids regulate gene expression levels differently in subjects carrying the PPARα L162V polymorphism. Genes & Nutrition, 4(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-009-0129-2

Spooner, M. H., & Jump, D. B. (2019). Omega-3 fatty acids and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults and children. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 22(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000539

Superko, H. R., Superko, A. R., Lundberg, G. P., Margolis, B., Garrett, B. C., Nasir, K., & Agatston, A. S. (2014). Omega-3 Fatty Acid Blood Levels Clinical Significance Update. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports, 8(11). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-014-0407-4

Surette, M. E. (2008). The science behind dietary omega-3 fatty acids. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(2), 177–180. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.071356

Wang, T., Xi, Y., Raji, A., Crutchlow, M., Fernandes, G., Engel, S. S., & Zhang, X. (2024). Overall and subgroup prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and prevalence of advanced fibrosis in the United States: An updated national estimate in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2018. Annals of Hepatology, 29(1), 101154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2023.101154

Yan, J.-H., Guan, B.-J., Gao, H.-Y., & Peng, X.-E. (2018). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicine, 97(37), e12271. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000012271

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH, is a licensed General Practitioner and Public Health Expert. She currently serves as a physician in private practice, combining clinical care with her passion for preventive health and community wellness.