Stages of Passing a Kidney Stone: What to Expect at Each Step

Written By

Abel Tamirat, MD

Written By

Abel Tamirat, MD

Kidney stones are a common and often painful condition. They form when minerals in the urine crystallize and stick together. A stone may sit quietly in the kidney for weeks or months before moving into the urinary tract. Once it starts moving, the pain can be intense.

Most small stones pass on their own, but knowing what to expect can make the process easier. In this article, you'll learn about the four stages of passing a kidney stone, what symptoms are common at each stage, and how to manage pain and prevent future stones.

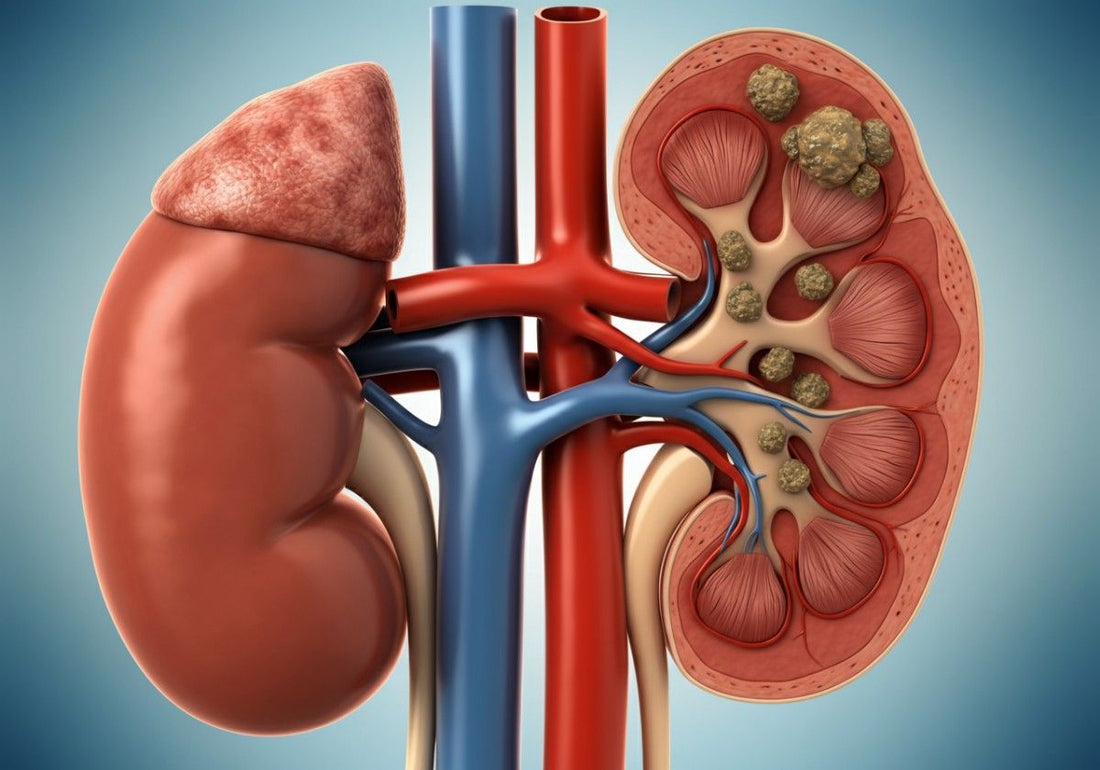

What is a kidney stone?

A kidney stone is a solid clump of minerals and salts that forms inside the kidney. These minerals usually dissolve in urine, but when urine is too concentrated, they can bind together and form crystals. Over time, those crystals can grow into a stone.

The most common type is a calcium oxalate stone, but others include uric acid, struvite, or cystine stones. Your risk of forming stones increases if you’re dehydrated, follow a high-sodium or high-protein diet, or have a family history of kidney stones.

Learn more about what size of kidney stone requires surgery if you’re unsure when to seek help.

What are the 4 stages of passing a kidney stone?

The process follows four key stages:

-

Silent formation in the kidney

-

Movement into the ureter

-

Travel down the ureter toward the bladder

-

Passage through the urethra and out of the body

Each stage brings different symptoms. Here’s what happens at each step.

f you’re prone to kidney issues, consider using an at-home kidney function test to monitor changes early.

Stage 1: Formation in the kidney

This is the quietest stage. A stone begins to form inside your kidney without causing symptoms. You likely won’t know it’s there.

Stones can be found accidentally during imaging tests for unrelated issues. Many people have no idea they’ve developed a stone until it begins to move and cause discomfort.

At this point, the stone may remain harmless if it stays in the kidney and doesn't block urine flow. However, over time, it may grow or start moving into the urinary tract.

Stage 2: Entry into the ureter

Pain usually begins when the stone enters the ureter, the thin tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder. The ureter is narrow, and even small stones can cause severe pain as they move through it.

Common symptoms

-

Sharp, cramping pain in the back or side

-

Pain that may move to the lower abdomen or groin

-

Waves of pain that come and go

-

Blood in urine (it may appear pink or red)

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Burning or discomfort while urinating

-

Urgency to urinate, even when the bladder is empty

If you notice blood in your urine, it’s important not to ignore it.

Pain in this stage is often described as one of the most intense types of pain. It can last from minutes to hours and may come in waves depending on the stone’s movement.

Stones smaller than 5 mm often pass naturally within a few days. Larger stones may take longer or require medical treatment, such as lithotripsy or ureteroscopy.

Stage 3: Travel down the ureter

As the stone continues its descent toward the bladder, pain often becomes less intense but can still be uncomfortable. The lower part of the ureter is slightly wider, which may help the stone move more easily.

Possible symptoms

-

Dull or shifting pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis

-

Pressure in the bladder

-

Frequent urge to urinate

-

Pain or burning while urinating

-

Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

During this stage, staying hydrated is important. Drinking more fluids helps flush the stone toward the bladder. You can also monitor hydration by checking your urine color or using urine specific gravity tests.

Stage 4: Stone enters the bladder and passes out

When the stone reaches the bladder, symptoms usually improve. From here, the stone is passed through the urethra during urination.

This stage can still be uncomfortable, especially for men, who have longer urethras.

What to expect

-

A brief, sharp pain during urination

-

A gritty or sandy feeling in the urine

-

Visible fragments or the stone itself in the toilet

-

Relief from previous pain

-

Soreness or tenderness afterward

After passing a stone, your doctor may ask you to collect it using a urine strainer. Analyzing the stone helps determine what it's made of and how to prevent more in the future.

How long does it take to pass a kidney stone?

That depends on the size of the stone and where it is located.

-

Stones smaller than 4 mm: often pass in 1 to 2 weeks

-

Stones 5 to 6 mm: may take 2 to 3 weeks

-

Stones larger than 6 mm: often need medical treatment

If a stone hasn't passed within 4 to 6 weeks, your doctor may recommend removal.

When should you call your doctor?

While many kidney stones pass naturally, some situations require medical attention.

Call your doctor if you have:

-

Severe pain that doesn’t improve with medicine

-

Fever over 100.4°F (38°C)

-

Difficulty urinating or not passing urine

-

Vomiting or dehydration

-

Blood in your urine with clots

-

Only one kidney or a known kidney disease

If you’re pregnant and experiencing symptoms, contact your provider immediately. Kidney stones in pregnancy need special care.

If you have chronic kidney disease, this may affect your treatment options.

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

Your doctor may use the following tests:

-

Urinalysis to check for blood, infection, or crystals

-

Blood tests to check kidney function, calcium, or uric acid

-

Imaging tests such as:

-

Non-contrast CT scan (most accurate)

-

Ultrasound (used in pregnancy)

-

X-ray (helps track stones if they are visible)

Together, these tools help your care team confirm the diagnosis and make a treatment plan.

What treatment options are available?

If the stone is small, you may only need to drink more fluids and take pain relievers. Over-the-counter options like ibuprofen or acetaminophen are usually enough.

Doctors may also prescribe:

-

Tamsulosin to help relax the ureter

-

Stronger pain medication if needed

-

Anti-nausea medication if you’re vomiting

If the stone doesn’t pass or is too large, your doctor may suggest:

-

Shock wave lithotripsy to break the stone into small pieces

-

Ureteroscopy to remove or laser the stone through a thin scope

-

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy to surgically remove very large stones through a small incision

Your care team will help you choose the safest option.

Surgical options are sometimes required when there's an obstructive kidney cyst or infection.

How can you prevent future kidney stones?

Prevention depends on the type of stone you had. Your doctor may recommend a 24-hour urine collection to check for high levels of calcium, oxalate, uric acid, or other substances.

General prevention tips

-

Drink at least 2.5 to 3 liters of water daily

-

Reduce sodium in your diet

-

Limit animal protein like red meat and shellfish

-

Eat calcium-rich foods with meals (not supplements unless advised)

-

Avoid high-oxalate foods like spinach, almonds, and chocolate

-

Use lemon or lime to increase urinary citrate

-

Take prescribed medications like thiazide diuretics or potassium citrate

Ask your doctor for a personalized prevention plan based on your test results.

For more details on diet and prevention, see our 7-day kidney stone diet chart.

Final thoughts

Most kidney stones pass naturally, especially those smaller than 5 mm. But the pain can be intense. Understanding each stage can help you manage symptoms, know what’s normal, and when to reach out for help.

Don’t ignore symptoms like fever, vomiting, or difficulty peeing. And once the stone passes, take steps to prevent it from coming back.

If you’re unsure about your symptoms or want to test from home, check out Ribbon Checkup’s at-home kidney health test.

Related Resources

-

What Size of Kidney Stone Requires Surgery?

Understand when a kidney stone may need more than just time to pass naturally. -

How Long Do Kidney Stones Last? Must Know

Learn about typical timelines for passing stones—and when to seek help. -

How Accurate Are Urine Tests for Kidney Stones? Your Guide to Diagnosis and Prevention

Explore how urine testing helps detect and manage kidney stones.

References

American Urological Association. (2014). Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. Journal of Urology, 192(2), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.006

Cleveland Clinic. (2024, February 26). Kidney stones: Causes, symptoms, diagnosis & treatment. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15604-kidney-stones

Khan, S. R., Pearle, M. S., Robertson, W. G., Gambaro, G., Canales, B. K., Doizi, S., Traxer, O., & Tiselius, H.-G. (2018). Kidney stones: An update on current concepts. Advances in Urology, 2018, Article 3068365. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3068365

Mayo Clinic. (2025, April 4). Kidney stones: Symptoms & causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/kidney-stones/symptoms-causes/syc-20355755

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (n.d.). Kidney stones. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/kidney-stones

National Kidney Foundation. (2025, July 24). Kidney stones. https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/kidneystones

Dr. Abel Tamirat is a licensed General Practitioner and ECFMG-certified international medical graduate with over three years of experience supporting U.S.-based telehealth and primary care practices. As a freelance medical writer and Virtual Clinical Support Specialist, he blends frontline clinical expertise with a passion for health technology and evidence-based content. He is also a contributor to Continuing Medical Education (CME) programs.