Exploring the 4 Methods for Kidney Stone Removal: Benefits and Risks

Written By

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH

Written By

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH

Kidney stones affect millions of people each year. It causes severe pain and discomfort that can disrupt your daily life. When these mineral deposits grow too large or just don't pass naturally, medical intervention becomes necessary so you can restore your health and comfort.

This article explores the 4 methods for kidney stone removal. It walks you through each procedure, who benefits from a specific procedure, and what recovery actually looks like. So, whether you’re facing your first kidney stone or dealing with recurrent episodes, you need to know your treatment options. It will empower you to have meaningful conversation with your healthcare provider about your best options and way forward.

Key Insights

-

Shockwave lithotripsy treats stones up to 2 cm using sound waves from outside your body, with 70-90% success rates for appropriate candidates

-

Ureteroscopy offers 95% success for stones in the ureter and allows immediate removal without external incisions

-

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy removes large stones exceeding 2 cm through a small back incision, achieving 90% clearance in a single session

-

Medication can dissolve uric acid stones and prevent calcium stone growth, though it works slowly over weeks to months

-

Stone composition, size, and location determine which removal method works best, not patient preference alone

-

Drinking 2.5 to 3 liters of water daily cuts your risk of future stones by up to 60%

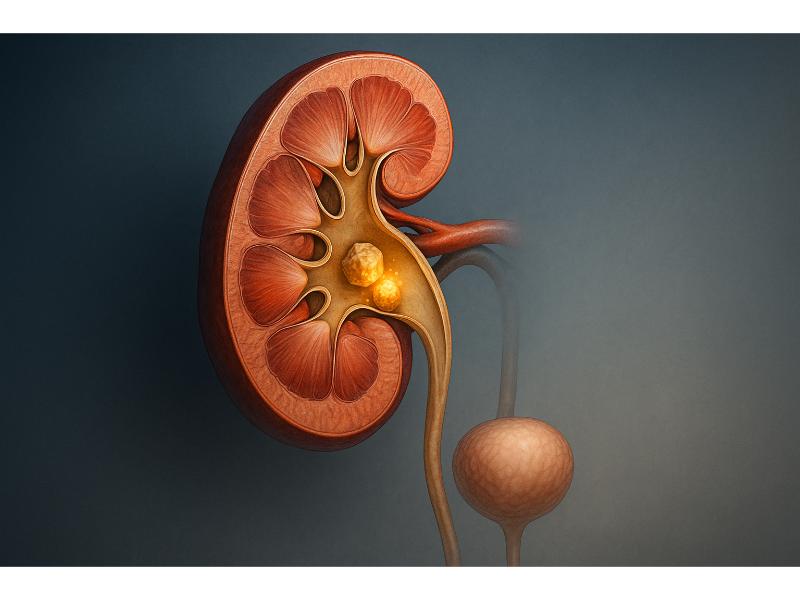

What Are Kidney Stones?

Kidney stones are hard mineral deposits that form inside your kidneys when your urine contains more crystal-forming substances than your urine can dilute. These substances include:

-

Calcium

-

Oxalate

-

Uric Acid

Your kidneys filter waste from your blood and create urine. But when waste products become concentrated, they can crystallize and stick together.

The stones can be as tiny as a grain of sand or as large as a golf ball. Small stones often pass through your urinary tract without causing any problems. Larger stones, however, can get stuck in the tubes that carry urine from your kidneys to your bladder (ureters), which blocks the urine flow and causes significant pain.

Your body normally keeps these substances balanced and flowing through your urinary system. But when this balance is disrupted, stones begin forming. Factors involved in this disruption include:

-

Dehydration

-

Diet

-

Medical conditions

-

Genetic factors

The process can take weeks, months, or even years depending on various factors affecting your body chemistry.

What Are The Types of Kidney Stones?

Understanding what type of kidney stone you have can help your doctor choose the most effective removal method. There are four main types that account for nearly all types of stones:

-

Calcium stones make up 80% of all kidney stones. They form when calcium combines with oxalate or phosphate in your urine. High oxalate levels from certain foods, excess in vitamin D, or intestinal conditions increases your risk.

-

Uric acid stones develop when your urine becomes too acidic. They affect people who eat high-protein diets, have gout, or undergo chemotherapy. These stones are the only type that medication can sometimes dissolve completely.

-

Struvite stones grow quickly and get large, often forming after urinary tract infections. Bacteria that can cause these infections change your urine chemistry, creating an environment where struvite crystals develop rapidly.

-

Cystine stones are rare and result from a genetic disorder called cystinuria. This inherited condition causes your kidneys to release too much cystine into your urine. These stones often recur and require ongoing management.

Your doctor identifies the stone type through laboratory tests after passing or removal. This information guides both immediate treatment and long-term prevention strategies tailored to your specific stone chemistry.

What Are the Common Symptoms, Signs, and Clinical Diagnosis?

Kidney stone symptoms appear suddenly and may intensify as the stone moves. The pain often starts in your back or side just below the ribs and radiates to your lower abdomen and groin. Many people describe it as waves of severe pain that come and go as the stone shifts in location.

Common warning signs include:

-

Sharp pain that prevents you from finding a comfortable position

-

Pink, red, or brown urine indicating blood

-

Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

-

Nausea and vomiting accompanying the pain

-

Frequent urination or feeling an urgent need to urinate

-

Fever and chills if infection develops

-

Burning sensation when urinating

Your doctor will diagnose kidney stones through several methods. Blood tests check for high calcium or uric acid levels. Urine tests over 24 hours measure stone-forming minerals in your urine. Imaging provides the clearest picture. CT scans detect even small stones and show their exact location and size. Ultrasound offers a radiation-free alternative, which is especially useful for pregnant women and children. X-rays can spot most stones but may miss some types.

Your healthcare provider may also perform a physical exam like pressing your abdomen and back to locate the stone through the pain that it can generate. This helps distinguish kidney stones from other conditions that may cause similar symptoms.

Why Stone Removal May Be Needed?

Most small kidney stones less than 5mm in size may pass spontaneously 68% of the time. You can manage the symptoms, particularly the pain, at home with fluids and over-the-counter pain medications while waiting for the stone to pass. Your doctor will monitor your progress to confirm the stone passes completely.

Medical removal becomes necessary when stones cause complications or refuse to pass on their own. You need intervention if:

-

The stones between 5-10mm in size only have 47% chance of passing spontaneously, which may mean that the remaining 53% will not pass naturally as expected

-

Severe pain persists despite medication

-

The stone partially or completely blocks urine flow, which may cause kidney swelling

-

You develop urinary tract infection alongside the stone

-

Your kidney function starts declining

-

You only have one working kidney that’s being affected

-

Bleeding persists or worsens

-

Your job requires you to be pain-free and fully functional

Delaying necessary treatment can lead to permanent kidney damage. A blocked kidney swells with trapped urine, potentially causing irreversible harm to the delicate filtering structures inside. Infections can spread to your bloodstream, creating a life-threatening condition called sepsis.

What Are the Risks, Complications, Treatment Rationale?

Every kidney stone removal method carries specific risks that you should discuss with your doctor. Common complications across procedures include infection, bleeding, and injury to surrounding organs. Your personal health status, stone characteristics, and chosen procedure affect your individual risk level.

General risks include:

-

Infection requiring antibiotics or additional treatment

-

Blood in urine that usually resolves within days

-

Fragments remaining that need another procedure

-

Injury to the ureter or kidney during stone removal

-

Temporary kidney function changes

-

Pain during recovery despite medication

Doctors choose the treatment based on multiple factors working together. Stone size matters the most when it comes to treatment options.

Stones that are less than 10 mm respond well to less invasive approaches. Their location, however, influences the decision because stones in different parts of the urinary system require different access methods. Your overall health affects which procedures you can safely undergo. Stone composition determines whether medication might work or if mechanical removal is necessary.

The treatment rationale balances effectiveness against invasiveness. Your doctor aims for the least invasive method that can still achieve complete stone removal. This approach minimizes your recovery time while maximizing the success rates. Sometimes a more invasive approach makes sense initially because it prevents the need for multiple interventions later.

Quick Comparison Table: 4 Methods for Kidney Stone Removal

|

Method |

How It Works |

When Is It Used |

Key Benefits |

Risk Considerations |

|

Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL) |

Breaks stones with shock waves |

Small to medium stones |

Non-invasive |

Not for large and hard stones |

|

Ureteroscopy |

Scope and laser to fragment the stones |

For stones located in the ureter |

Precise, quick recovery |

May need stent |

|

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy |

Keyhole surgery through your back |

For large and hard stones |

Effective on big stones |

Invasive, longer recovery |

|

Medication-based treatment |

Dissolves and suppresses small stones |

Certain small stones |

Non-surgical |

Slow, not for all stones |

Method 1: Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL)

Shockwave lithotripsy uses focused sound waves to break kidney stones into small pieces that pass naturally through your urine. A machine called a lithotripter generates these shock waves and aims them precisely at your stone using X-ray or ultrasound guidance. The waves travel through your body tissue without causing damage because soft tissue doesn't absorb the energy.

The procedure typically takes 45 to 60 minutes. You lie on a cushioned table or in a water bath while the machine delivers 1,000 to 2,000 shock waves. Most patients receive sedation or light anesthesia to keep you comfortable, though you remain awake and can usually go home the same day.

After treatment, stone fragments pass over several days to weeks. You may notice:

-

Blood in your urine for a few days

-

Mild pain or aching in your back or abdomen

-

Bruising on your back or side where shock waves entered

-

Nausea during fragment passage

Success rates range from 70% to 90% for stones smaller than 2 cm. The procedure works best on stones in your kidney rather than your ureter. You might need a repeat session if fragments remain too large to pass.

SWL offers major advantages. It requires no incisions and causes minimal discomfort compared to surgery. Recovery happens quickly, with most people returning to normal activities within two to three days. The outpatient nature means no hospital stay in most cases.

However, limitations exist. Hard stones composed of calcium oxalate monohydrate or cystine resist shock waves and fragment poorly. Large stones over 2 cm rarely break into pieces small enough to pass easily. Obesity can interfere with shock wave focusing. Your kidney's anatomy might make accurate targeting difficult.

Who Is an Ideal Candidate? Stone Types and Sizes Treated.

You're an ideal candidate for shockwave lithotripsy if you have a stone between 4 mm and 2 cm located in your kidney or upper ureter. The stone should be visible on X-ray and positioned where shock waves can reach it effectively. Your overall health matters too, you need normal blood clotting and no active urinary tract infection.

Best stone types for SWL include:

-

Calcium phosphate stones fragment easily under shock waves

-

Uric acid stones when they're not too large

-

Softer calcium oxalate stones that haven't hardened extensively

You're not a good candidate if you're pregnant, as shock waves could harm the fetus. People with bleeding disorders or those taking blood thinners face higher bleeding risks. Severe obesity makes targeting difficult because shock waves lose focus traveling through excess tissue. Kidney abnormalities or stones blocking urine flow completely require different approaches.

Your doctor considers stone density measured on CT scans. Stones measuring over 1,000 Hounsfield units on imaging rarely break well with SWL. In these cases, other removal methods work better from the start, saving you time and avoiding failed procedures.

Method 2: Ureteroscopy

Ureteroscopy involves passing a thin, flexible telescope called a ureteroscope through your urethra and bladder into your ureter. This scope contains a camera that lets your doctor see the stone directly. A laser fiber threaded through the scope breaks the stone into tiny fragments, which your doctor removes with a small basket or lets pass naturally.

The procedure happens under general or spinal anesthesia and takes 30 to 90 minutes. You feel nothing during the operation. Your doctor may place a temporary stent (a small tube) in your ureter after removing the stone to keep urine flowing while swelling subsides. This stent stays in place for a few days to weeks.

Ureteroscopy excels at treating stones in your ureter, the tube connecting your kidney to your bladder. It reaches stones anywhere along this path. The procedure achieves 95% success rates for stones under 1 cm. Modern flexible ureteroscopes can navigate into your kidney to treat stones there too, though this requires more expertise.

Recovery advantages include:

-

No external incisions means no visible scars

-

Hospital discharge the same day or next morning

-

Return to work within three to five days for most people

-

Less pain than surgical approaches

-

Immediate stone removal rather than waiting for passage

Potential issues include stent discomfort. Many patients report urgency, frequency, and bladder spasms while the stent remains in place. Blood in your urine is normal for a few days. Rarely, the ureter can be injured during scope insertion, especially with very large stones. Infection affects 2% to 10% of patients despite preventive antibiotics.

The laser used to break stones generates heat. Your doctor flushes your ureter with fluid continuously to prevent thermal injury. Modern holmium lasers fragment stones efficiently while protecting surrounding tissue. The fragments produced are small enough to pass easily or can be extracted during the procedure.

Your doctor may recommend ureteroscopy over other methods when you have hard stones that resist shock waves, stones causing severe symptoms that need immediate relief, or when you've already tried SWL without success. The procedure works regardless of your body size, making it ideal for obese patients.

Method 3: Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy treats large or complex kidney stones through a small incision in your back. A surgeon creates a narrow tunnel directly into your kidney, inserts a scope called a nephroscope, and breaks up stones using ultrasonic, pneumatic, or laser energy. The stone pieces get suctioned out immediately.

This procedure requires general anesthesia and hospitalization for one to three days. Surgery takes two to three hours. The surgeon uses X-ray or ultrasound guidance to place the tunnel precisely, minimizing kidney tissue damage. A tube called a nephrostomy stays in place temporarily to drain urine and any remaining stone fragments.

PCNL handles situations other methods cannot, such as:

-

Stones larger than 2 cm

-

Staghorn calculi that branch throughout your kidney

-

Stones that failed other treatments

-

Multiple large stones in one kidney

-

Hard stones resistant to shock waves

Success rates vary from 71-100% depending on various factors. This beats multiple sessions of other treatments for large stones. Your doctor can see and extract stones directly, ensuring thorough clearance.

Recovery takes longer than less invasive options. You'll experience:

-

Moderate pain at the incision site for several days

-

Blood in urine that gradually clears

-

Fatigue for one to two weeks

-

Activity restrictions for two to four weeks

-

Follow-up imaging to confirm complete stone removal

Complications occur more frequently than with SWL or ureteroscopy because the procedure is more invasive. Bleeding affects 0% to 20% of patients, usually resolving without intervention. Severe bleeding requiring transfusion happens in 1% to 3% of cases. Infection risk increases compared to other methods. Injury to surrounding organs like your colon or lung rarely occurs but requires immediate treatment.

Despite these risks, PCNL remains the treatment for large kidney stones. It removes stones that would otherwise cause ongoing pain, repeated infections, and progressive kidney damage. Your surgeon's experience significantly affects outcomes, so this procedure typically happens at larger medical centers with specialized urologists.

Modern techniques make PCNL safer and less invasive than older approaches. Mini-PCNL uses smaller instruments through a narrower tunnel, reducing bleeding and pain. Ultra-mini and micro-PCNL push this further for carefully selected cases. These variations maintain high success rates while improving recovery experiences.

Method 4: Medication-Based Treatment

Certain kidney stones can be treated with medication rather than surgery. These oral drugs either dissolve stones or prevent new ones from forming, depending on the stone’s composition.

Uric Acid Stones

These dissolve best with potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate, which make urine more alkaline (pH 6.5–7.0). Taken two to four times daily, these drugs gradually dissolve stones over weeks to months. Treatment continues until imaging confirms complete resolution.

Cystine Stones

Thiol drugs such as tiopronin or penicillamine bind to cystine, keeping it dissolved in urine. They work more slowly than for uric acid stones and require monitoring for side effects like rash, fever, or blood changes.

Calcium Stones

These cannot be dissolved but can be prevented from growing. Thiazide diuretics lower urinary calcium, while potassium citrate increases citrate levels to block stone formation. This approach suits smaller, stable stones.

Monitoring and Duration

Medical treatment typically takes three to six months, with regular:

-

Urine tests (pH and stone-forming chemicals)

-

Imaging every 1-3 months

-

Blood tests for side effects

-

Symptom tracking

Benefits and Limitations

This method avoids surgery and hospital visits, making it ideal for patients unable to tolerate anesthesia. However, it’s less effective for calcium oxalate stones, requires strict medication adherence, and carries potential side effects. Progress is slow, and missing doses or skipping follow-ups can cause setbacks.

Combined Approach

Doctors may pair medication with watchful waiting for small, symptom-free stones, monitoring stability and intervening surgically only if the stone grows or causes problems.

What Are Other Treatment Modalities for Kidney Stones?

Some kidney stone cases need special techniques beyond the main four methods. These options are used when standard treatments have limits or your case needs a customized approach.

-

Flexible ureteroscopy with laser fragmentation

This advanced technique uses a flexible scope to reach hard-to-access kidney areas. A laser breaks stones into fine dust that passes easily, making it ideal for stones in the kidney’s lower pole.

-

Robot-assisted stone removal

Robotic systems let surgeons control precise instruments with improved vision and movement. This is useful for complex cases requiring delicate work around kidney structures.

-

Laparoscopic stone removal

Used when other treatments fail or aren’t possible, this involves several small incisions and a camera-guided approach. It’s suited for large or unusually positioned stones, or when direct kidney access is risky.

-

Open surgery

Now rare, open surgery is reserved for extremely difficult cases such as massive staghorn stones, severe kidney abnormalities, or failed minimally invasive attempts. Though recovery takes weeks, it ensures complete stone removal.

-

Combination therapy

Doctors may combine methods. For example, using shock wave lithotripsy to break a large stone, followed by ureteroscopy to remove remaining fragments. This staged approach balances safety and effectiveness.

-

Medical therapy with alpha blockers

Drugs like tamsulosin relax the ureter muscles, helping stone fragments pass more easily after procedures. Studies show they speed up stone clearance and improve success rates.

How to Make Informed Treatment Decisions?

Making informed decisions may sound easy but it requires patience and critical analysis of your options:

Learn About Your Stone

Ask your doctor:

-

What size is it?

-

Where is it located?

-

What type of stone is it?

-

Can it pass naturally or does it need removal?

-

How urgent is treatment?

Knowing these helps identify which treatments fit your situation.

Consider Your Lifestyle

Think about your job, family, and recovery needs.

-

Need a quick return to work? Choose a less invasive option for faster recovery

-

Can you manage time off or arrange help at home? That affects your choice.

Check Financial Factors

Costs vary by treatment. Ask about insurance coverage, copays, and total expenses (hospital, surgeon, anesthesia, follow-ups).

Know Your Risk Tolerance

Would you rather choose a simpler option with lower success rates or a more invasive one with a higher chance of complete removal? Pick what aligns with your comfort level.

Get a Second Opinion

Another urologist may suggest different options—especially for large or complex stones. It’s normal and helpful to compare perspectives.

Ask About Experience

Surgeon skill matters. Ask how often they perform the procedure you’re considering.

Understand the Full Plan

If the first treatment doesn’t work, what’s next? Knowing backup options avoids surprises.

Consider Timing

Some stones need quick treatment; others allow time to plan. Use available time to research and prepare, not rush.

How to Prevent Kidney Stones and What Are Lifestyle Modifications to Adapt?

Preventing kidney stones is as important as treating them, about half of patients develop another stone within 5 years without prevention. The right lifestyle and medical steps can greatly cut this risk.

Hydration

-

Drink enough fluids to produce at least 2.5 liters of urine daily (usually 3-4 liters of fluid intake although this depends on your level of activity and fluid losses)

-

Plain water is best

-

Avoid sugary drinks and limit caffeine intake

-

Add lemon juice to water for extra citrate, which helps prevent calcium stones

-

Check urine color: pale yellow or clear means good hydration; dark yellow means drink more.

Diet

-

Calcium: Keep normal intake (1,000–1,200 mg/day) from food; low calcium increases oxalate absorption.

-

Oxalate: Limit high-oxalate foods (spinach, rhubarb, nuts, chocolate, tea); moderate, don’t eliminate.

-

Sodium: Keep below 2,300 mg/day; avoid processed and restaurant foods.

-

Animal protein: Limit to 6–8 oz/day if you form uric acid or calcium stones.

-

Sugar: Reduce intake, especially high-fructose corn syrup, which raises urinary calcium and uric acid.

-

Vitamin C: Keep supplements under 1,000 mg/day; prefer food sources.

Medication (if lifestyle isn’t enough)

-

Thiazide diuretics lower urinary calcium; cut recurrence by ~50%.

-

Potassium citrate raises urinary citrate and pH to prevent calcium and uric acid stones

-

Allopurinol reduces uric acid for stones containing uric acid

-

Tiopronin keeps cystine dissolved in cystinuria, which requires lifelong use

Testing & Monitoring

-

Do a 24-hour urine test to identify personal stone risk factors and tailor prevention.

-

Keep a stone diary to log fluid intake, diet, symptoms, and stone events.

-

Use at-home urine test strips to have an overview of your kidney status

Lifestyle

-

Obesity increases stone risk. Aim to lose 1–2 lbs/week through steady diet and exercise.

-

At least 150 minutes of moderate activity weekly to improve kidney health and circulation.

Support & Follow-up

-

Schedule regular visits with your urologist or nephrologist for monitoring.

-

Join support groups (online or local) for shared advice and motivation.

-

Work with a registered dietitian experienced in kidney stone prevention to create sustainable meal plans.

What It's Like Living With and After Kidney Stones

Living with kidney stones means making changes to your daily routine to prevent them from coming back while also handling the emotional side of the condition. Many people feel anxious about having another stone, especially if their first one caused severe pain. This fear is natural but can be managed with preparation and the right attitude.

Your daily life focuses on prevention. You get used to carrying a water bottle and keeping track of how much you drink. You plan ahead for times when water might not be easy to find. Eating out takes more thought as you pay attention to sodium and oxalate levels. These habits may feel difficult at first but soon become part of your routine.

Exercise is still important after kidney stones. Most people return to normal activities within days or weeks after treatment. Listen to your body, increase activity slowly, and avoid contact sports for a short time after procedures. Staying active supports overall health and helps prevent stones.

Traveling needs extra care. Bring enough water and your medications, especially when flying or visiting hot places. Know where nearby medical facilities are and consider carrying a card that lists your stone history and current medications.

Kidney stones can also affect your emotions. The fear of another episode can make you worry, especially when away from medical help. Talking with a counselor can help you manage these feelings. Remember that following prevention steps greatly lowers your risk.

Work life usually continues with little interruption. Most people can return to work within a few days, though physical jobs may need more recovery time. Let your employer know if you need time for appointments or recovery. Many workplaces offer flexibility for health conditions.

Sexual activity can resume once pain is gone and any stent has been removed. Some people may feel temporary discomfort, but it improves as healing continues. If problems last, talk to your doctor.

Women planning pregnancy should discuss their kidney stone history with their doctor. Pregnancy increases stone risk, so your obstetrician may suggest preventive steps and closer monitoring. Most stones can be safely managed during pregnancy.

The long-term outlook is positive. With proper prevention, many people never have another stone. Even if stones recur, they are often less frequent and less painful. Advances in medicine continue to improve treatment and prevention.

Regular checkups with your urologist are important. These visits help catch new stones early and allow you to review your prevention plan. Report any new symptoms right away.

Support from family, friends, and online communities makes living with kidney stones easier. Sharing experiences helps you cope better and reminds you that you are not alone.

Related Resources

Can Kidney Stones Lead to Constipation? Understanding the Connection

How Accurate Are Urine Tests for Kidney Stones? Your Guide to Diagnosis and Prevention

Quick Summary Box

-

Four main removal methods exist: shockwave lithotripsy for small stones, ureteroscopy for precise removal, percutaneous nephrolithotomy for large stones, and medication for specific types

-

Stone size, location, and composition determine which treatment works best, with success rates ranging from 70% to 95% depending on the method

-

Less invasive procedures like SWL and ureteroscopy allow same-day discharge and quick recovery, while PCNL requires hospitalization but handles larger stones

-

Prevention through adequate hydration (2.5 to 3 liters of urine daily), dietary modifications, and medication reduces recurrence risk by up to 60%

-

Recovery varies from days for minimally invasive procedures to weeks for surgical approaches, with most people returning to normal activities relatively quickly

-

Regular follow-up care, 24-hour urine testing, and personalized prevention plans help maintain long-term stone-free status

References

CDC. (2023, December 20). Physical activity for adults: An overview. Physical Activity Basics; CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/guidelines/adults.html

Curhan, G. C., & Goldfarb, D. S. (2023). Thiazide Use for the Prevention of Recurrent Calcium Kidney Stones. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.0000000000000399

Cystine Kidney Stones. (2025, September 9). National Kidney Foundation. https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/cystine-kidney-stones

Erhan Erdoğan, Gamze Şimşek, Alper Aşık, Göksu Sarıca, & Kemal Sarıca. (2025). Impact of advanced lithotripter technology on SWL success: ınsights from Modulith SLK ınline outcomes. World Journal of Urology, 43(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-025-05517-4

Extra-corporal Shock Wave Lithotripsy | ESWL. (2023, July 26). Melbourne Urology Centre. https://melbourneurologycentre.com.au/extra-corporal-shock-wave-lithotripsy/

Favus, M. J., & Feingold, K. R. (2018). Kidney stone emergencies (K. R. Feingold, B. Anawalt, A. Boyce, G. Chrousos, K. Dungan, A. Grossman, J. M. Hershman, G. Kaltsas, C. Koch, P. Kopp, M. Korbonits, R. McLachlan, J. E. Morley, M. New, L. Perreault, J. Purnell, R. Rebar, F. Singer, D. L. Trence, & A. Vinik, Eds.). PubMed; MDText.com, Inc. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278956/

FDA. (2020). Sodium in your diet. FDA. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/sodium-your-diet

Gücük, A. (2014). Usefulness of hounsfield unit and density in the assessment and treatment of urinary stones. World Journal of Nephrology, 3(4), 282. https://doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v3.i4.282

Huang, J.-S., Xie, J., Huang, X.-J., Yuan, Q., Jiang, H.-T., & Xiao, K.-F. (2020). Flexible ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy for renal stones 2 cm or greater: A single institutional experience. Medicine, 99(43), e22704. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022704

John Hopkins Medicine. (2019). Ureteroscopy. John Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/ureteroscopy

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2019). Kidney Stones. Johns Hopkins Medicine; Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/kidney-stones

Kc, M., & Leslie, S. W. (2021). Uric Acid Nephrolithiasis. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560726/

Khan, S. R., Pearle, M. S., Robertson, W. G., Gambaro, G., Canales, B. K., Doizi, S., Traxer, O., & Tiselius, H.-G. (2016). Kidney stones. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.8

Liss, M. A., Reveles, K. R., Tipton, C. D., Gelfond, J., & Tseng, T. (2023). Comparative Effectiveness Randomized Clinical Trial Using Next-generation Microbial Sequencing to Direct Prophylactic Antibiotic Choice Before Urologic Stone Lithotripsy Using an Interprofessional Model. European Urology Open Science, 57, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2023.09.008

Manzoor, H., & Saikali, S. W. (2021). Renal Extracorporeal Lithotripsy. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560887/

Monroy, R. E., Proietti, S., Leonardis, F. D., Stefano Gisone, Scalia, R., Mongelli, L., Franco Gaboardi, & Giusti, G. (2025). Complications in Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. Complications, 2(1), 5–5. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications2010005

Nephrostomy - InsideRadiology. (2017, July 26). InsideRadiology. https://www.insideradiology.com.au/nephrostomy/

Schaefer, B., Garba, A., & Wu, X. (2025). Outcomes of Tiopronin and D-Penicillamine Therapy in Pediatric Cystinuria: A Clinical Comparison of Two Cases. Reports, 8(3), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030163

Solan, M. (2018, March 8). 5 things that can help you take a pass on kidney stones - Harvard Health Blog. Harvard Health Blog. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/5-things-can-help-take-pass-kidney-stones-2018030813363

Ureteroscopy Specialists in Atlanta | Minimally Invasive. (2025). Advanced Urology. https://www.advancedurology.com/procedures/ureteroscopy

Wood, K. D., Gorbachinsky, I., & Gutierrez, J. (2014). Medical expulsive therapy. Indian Journal of Urology : IJU : Journal of the Urological Society of India, 30(1), 60–64. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.124209

Yılmaz, S., Topcuoğlu, M., & Demirel, F. (2023). Evaluation of Factors Affecting Success Rate in Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: A Five-Year Experience. Journal of Urological Surgery, 10(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.4274/jus.galenos.2023.2022.0068

Young, M., & Leslie, S. W. (2020). Percutaneous Nephrostomy. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493205/

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH, is a licensed General Practitioner and Public Health Expert. She currently serves as a physician in private practice, combining clinical care with her passion for preventive health and community wellness.