Understanding A Staghorn Kidney Stone: A Complete Guide to Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention

Written By

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH

Written By

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH

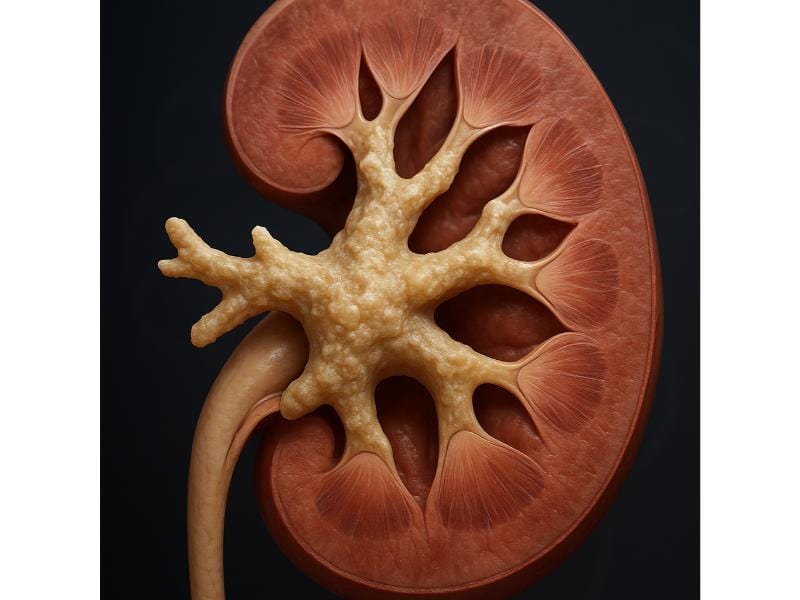

A staghorn kidney stone is one of the most serious types of kidney stones. They get their name from their branching structure that looks like a deer's antlers. These large stones fill the kidney's collecting system and can cause severe problems if not treated. Knowing about staghorn stones helps you spot warning signs early and get medical care. This guide covers symptoms, causes, treatment options, and long-term kidney health effects.

Key Insights

-

Staghorn kidney stones are large, branching stones in the kidney's central collecting system, usually caused by chronic urinary tract infections with specific bacteria

-

These stones can stay silent for long periods but may cause flank pain, blood in urine, frequent infections, and fever when problems arise

-

Untreated staghorn stones can damage kidneys, cause chronic infections, lead to sepsis, and potentially cause kidney failure

-

Early detection through imaging and quick treatment greatly improves outcomes and protects kidney function

What is a Staghorn Kidney Stone?

A staghorn kidney stone is a large stone that branches throughout the kidney's collecting system. It looks like stag antlers when viewed on imaging tests. These stones form in the renal pelvis and spread into at least two calyces of the kidney.

Staghorn stones make up about 10-15% of all kidney stones but are much more serious than typical stones. Unlike smaller stones that might pass through the urinary tract, staghorn stones grow too large to exit on their own. They can take up large portions of the kidney's interior space.

The stone has several key features:

-

Most staghorn stones are made of struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate). Some form from calcium oxalate or uric acid

-

These stones typically measure 2-3 centimeters or larger. Some grow to fill the entire renal collecting system

-

The stone branches into multiple sections, creating a cast of the kidney's internal structure

-

Staghorn stones can develop over months to years, depending on underlying conditions

Women get this condition more often than men, with a ratio of about 2:1. People with repeated urinary tract infections face higher risk for developing these stones.

What Are the Symptoms of Staghorn Kidney Stones?

Staghorn kidney stones can cause different symptoms or stay silent for years. Your symptoms depend on the stone's size, location, and whether infections are present. Many people don't know they have a staghorn stone until problems develop.

Common symptoms include:

-

Flank pain

-

Hematuria

-

Recurrent UTIs

-

Fever and chills

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

-

Frequent urination

-

Pain during urination

Some patients have vague symptoms like general tiredness, loss of appetite, or unexplained weight loss. Just because you don't have severe pain doesn't mean the stone isn't dangerous. Many staghorn stones cause little discomfort while quietly damaging kidney tissue.

What Are the Causes of Staghorn Kidney Stones?

Staghorn kidney stones form through specific processes that differ from typical kidney stones. Understanding these causes helps you identify risk factors and prevent future stones.

Primary causes include:

-

Chronic bacterial infections (e.g., Proteus, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas) that split urea into ammonia. This will increase urine pH and promote struvite crystal formation.

-

Metabolic disorders

-

Poor urine drainage

-

Anatomical abnormalities

-

Dehydration

-

Family history

-

Previous kidney stones

The infection-stone cycle creates a dangerous situation. Bacteria thrive around the stone while the stone protects bacteria from antibiotics. This cycle can continue for years without surgical stone removal.

What Happens When a Kidney Stone Gets Stuck?

When a kidney stone gets stuck, it blocks the urinary tract and stops urine from flowing normally. The blockage triggers intense pain and can cause serious problems if not quickly addressed.

The blockage usually happens at narrow points in the urinary system:

-

Ureteropelvic junction (most common)

-

Mid-ureter

-

Ureterovesical junction

When blockage happens, urine backs up into the kidney, causing hydronephrosis (kidney swelling). The increased pressure damages delicate kidney tissues and triggers severe pain. Your kidney keeps making urine, but with nowhere to go, pressure builds fast.

Complications from a stuck stone include:

-

Severe colicky pain

-

Kidney infection

-

Kidney damage

-

Sepsis risk

-

Loss of kidney function

Medical help becomes necessary when stones stay stuck. Doctors may insert a stent to restore urine flow or perform procedures to break up or remove the stone. Time matters, the longer the blockage lasts, the greater the risk of permanent kidney damage.

When Does a Kidney Stone Hurt the Most?

Kidney stones hurt most when they're moving through the urinary tract or causing sudden blockage. Pain typically peaks when a stone enters the ureter and tries to pass through this narrow tube.

The timing of worst pain relates to specific stone movements:

-

Initial movement

-

Ureter passage

-

Narrowest points

The pain often comes in waves called renal colic. Between waves, you might feel dull aching, but the intense episodes can be unbearable. The pain may shift location as the stone moves, starting in the flank and radiating toward the groin as the stone descends.

Interestingly, once a small stone enters the bladder, pain often drops dramatically. The bladder has more space and stretches more easily than the ureter, so the stone causes less irritation. However, staghorn stones rarely move because of their size, so they may cause chronic dull pain rather than sudden intense episodes.

Why Do Kidney Stones Cause Excruciating Pain to Patients?

Kidney stones cause terrible pain through multiple mechanisms that activate some of the body's most sensitive pain pathways. The urinary tract contains many nerve endings that respond strongly to stretching and irritation.

The pain mechanisms include:

-

Ureteral spasm

-

Tissue stretching

-

Pressure buildup

-

Inflammation

-

Nerve compression

The kidney capsule (outer covering) cannot stretch much. So when urine backs up and the kidney swells, the capsule becomes tightly stretched. This activates pain receptors that send signals through nerves to your brain. The pain signal travels through the same nerve pathways that serve other belly and pelvic organs, which explains why kidney stone pain often spreads to unexpected areas.

The ureter's muscular contractions normally move urine smoothly downward. With a stone present, these contractions become more forceful and spasmodic, trying unsuccessfully to move the blockage. This creates the typical wave-like pattern of renal colic pain.

Your body also releases prostaglandins and other inflammatory substances in response to the stone. These chemicals sensitize nerve endings, making them fire more readily and intensely. This explains why anti-inflammatory medications often help reduce kidney stone pain alongside pain relievers.

Is There a Link Between Kidney Stones and Bladder Cancer?

Research shows a possible connection between kidney stones and bladder cancer, though the relationship is complex and not fully understood. Studies show that people with a history of kidney stones may face a slightly higher risk of developing bladder cancer compared to those without stones.

Several theories try to explain this link:

-

Repeated stone episodes or lasting stones may irritate the urinary tract lining over time, potentially leading to cellular changes

-

Both conditions share common risk factors like chronic dehydration, certain dietary patterns, and smoking

-

Chronic urinary tract infections linked with certain stones might contribute to cancer development

-

Lasting inflammation from stones could create conditions favorable for cancer cell development

A large population study found that kidney stone patients had about 1.5 times higher risk of bladder cancer. However, the actual risk stays low—most people with kidney stones never develop bladder cancer. The increased risk appears stronger in people with repeated stones or chronic urinary infections.

The link appears stronger for certain stone types, particularly those linked with chronic infection like struvite stones. Bladder cancer risk also increases with the number of stone episodes and the time since the first stone.

Despite this link, kidney stones do not directly cause bladder cancer. Instead, shared underlying factors or chronic inflammatory processes might contribute to both conditions. If you have a history of kidney stones, keeping up with regular follow-up care and reporting any concerning urinary symptoms helps catch potential issues early.

What Does Calcification in the Kidney Mean?

Calcification in the kidney means calcium deposits build up in kidney tissue. These deposits show up as bright white spots on X-rays or CT scans. They mark areas where calcium has crystallized outside its normal locations.

Kidney calcifications can occur in several forms:

-

Kidney stones

-

Vascular calcifications

-

Parenchymal calcifications

The condition develops through different mechanisms. Sometimes damaged kidney cells attract calcium deposits. Other times, high calcium levels in blood or urine cause buildup into tissue. Chronic inflammation, infection, or tissue death can also trigger calcification.

Common causes include:

-

Hypercalciuria

-

Hyperparathyroidism

-

Renal tubular acidosis

-

Vitamin D excess

-

Sarcoidosis

-

Milk-alkali syndrome

Calcifications may cause no symptoms, especially when limited. However, widespread nephrocalcinosis can harm kidney function over time. The deposits interfere with normal kidney filtering and concentration abilities. Some people get flank pain, blood in urine, or repeated urinary tract infections.

Calcifications can be seen in imaging studies. Plain X-rays may show them, but CT scans give the most detailed view. Treatment focuses on addressing the root cause rather than the calcifications themselves. Controlling calcium levels, treating infections, and managing metabolic disorders can prevent further calcification.

Can a 3 cm Ovary Cyst Hide a Kidney Stone on a CT Scan?

A 3 cm ovary cyst generally cannot hide a kidney stone on a CT scan because these structures exist in different body locations with distinct features on imaging. Modern CT technology easily tells apart different tissue densities and body structures in the belly and pelvis.

CT scans use X-ray beams to create detailed cross-sectional images. Different tissues absorb X-rays differently, creating contrast on the images:

-

Kidney stones appear very bright white structures since calcium strongly absorbs X-ray

-

Ovarian cysts appear as dark fluid-filled structures that don’t absorb X-rays well

-

Kidneys sit behind the abdominal cavity on either side of the spine

-

Ovary is positioned in the pelvis, usually several centimeters away from the kidney

Radiologists carefully examine all visible structures when reading CT scans. They look at kidneys, ureters, bladder, and surrounding organs using different imaging windows and reconstructions. A cyst near the ovary wouldn't physically block the view of the kidney on a CT scan because these organs don't overlap.

In rare situations, positioning or body type might make interpretation challenging. But modern CT technology includes multiple image reconstructions and viewing angles. If one view seems unclear, radiologists examine alternative views or slices to clarify findings.

The only scenario where confusion might arise is if both a kidney stone and ovarian cyst exist, and a rushed or incomplete reading focuses mainly on one finding. However, thorough CT scan reports carefully document all significant findings in all visible organs, not just the primary area of concern.

Can Kidney Stones Ever Affect Kidney Function?

Kidney stones can definitely affect kidney function, particularly when they cause blockage, infection, or stay in place for long periods. The degree of impact depends on stone size, location, duration, and whether one or both kidneys are affected.

Kidney stones impact function through several mechanisms:

-

Obstruction

-

Infection

-

Direct damage

-

Inflammation

-

Reduced blood flow

Sudden blockage from a stone typically causes temporary kidney function decline. Once the blockage is relieved, function often returns to normal or near-normal levels, especially if treatment happens quickly. However, lasting blockage for days to weeks can cause permanent damage.

Staghorn stones pose particular risks because they can silently damage kidneys over months or years. The stone's bulk takes up space where working kidney tissue should be. Chronic infection linked with struvite staghorn stones creates ongoing inflammation that progressively scars the kidney.

Studies show that people with repeated kidney stones face higher risk of chronic kidney disease compared to those without stones. Each stone episode potentially causes some kidney damage. Over time, cumulative damage from multiple stones can significantly harm function.

Your body's backup system provides some protection. You can function normally with just 30-40% of total kidney capacity. Even if one kidney becomes severely damaged from stones, the other kidney often compensates. However, stones affecting both kidneys or stones in a solitary kidney pose more serious threats to overall kidney function.

At-home urine testing can provide an overview of your kidney’s health. It may not be used as a diagnostic tool but it can be used as screening in between doctor’s appointments.

Quick Summary Box

-

Staghorn kidney stones are large, branching formations that fill the kidney's collecting system and require surgical removal—they cannot pass on their own

-

These stones affect women more than men and are commonly caused by chronic urinary tract infections with bacteria that create alkaline urine conditions

-

Symptoms range from none at all to severe flank pain, repeated infections, blood in urine, and fever, many people stay unaware until the stone causes complications

-

Untreated staghorn stones progressively damage kidney tissue through chronic pressure, infection, and inflammation, potentially leading to kidney failure over time

References

Cho, J. H., & Holley, J. L. (2013). Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder in a female associated with multiple bladder stones. BMC Research Notes, 6, 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-354

Favus, M. J., & Feingold, K. R. (2018). Kidney stone emergencies (K. R. Feingold, B. Anawalt, A. Boyce, G. Chrousos, K. Dungan, A. Grossman, J. M. Hershman, G. Kaltsas, C. Koch, P. Kopp, M. Korbonits, R. McLachlan, J. E. Morley, M. New, L. Perreault, J. Purnell, R. Rebar, F. Singer, D. L. Trence, & A. Vinik, Eds.). PubMed; MDText.com, Inc. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278956/

Flannigan, R. K., Battison, A., De, S., Humphreys, M. R., Bader, M., Lellig, E., Monga, M., Chew, B. H., & Lange, D. (2018). Evaluating factors that dictate struvite stone composition: A multi-institutional clinical experience from the EDGE Research Consortium. Canadian Urological Association Journal, 12(4), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.4804

Gaillard, F. (2022, May 27). Staghorn calculus (kidney) | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Radiopaedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/staghorn-calculus-kidney

National Kidney Foundation. (2022, July 13). Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR). National Kidney Foundation. https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/estimated-glomerular-filtration-rate-egfr

Patti, L., & Leslie, S. W. (2021). Acute Renal Colic. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431091/

Rule, A. D., Bergstralh, E. J., Melton, L. J., Li, X., Weaver, A. L., & Lieske, J. C. (2009). Kidney Stones and the Risk for Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN, 4(4), 804–811. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05811108

Staghorn Kidney Stones | Urology of Greater Atlanta. (n.d.). Https://Ugatl.com/. https://ugatl.com/services/kidney-stones/staghorn-kidney-stones/

Torricelli, F. C. M., & Monga, M. (2020). Staghorn renal stones: what the urologist needs to know. International Braz J Urol, 46(6), 927–933. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.99.07

Tseng, C.-W., Chen, W.-N. J., Juang, G.-D., & Hwang, T. I-Sheng. (2015). Staghorn calculi and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis associated with transitional cell carcinoma. Urological Science, 26(1), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urols.2014.12.006

Vaidya, S. R., Yarrarapu, S. N. S., & Aeddula, N. R. (2021). Nephrocalcinosis. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537205/

Jaclyn P. Leyson-Azuela, RMT, MD, MPH, is a licensed General Practitioner and Public Health Expert. She currently serves as a physician in private practice, combining clinical care with her passion for preventive health and community wellness.